Tay Bridge

After the piece on the Forth Bridge, I have had several requests to cover the other famous Scottish railway bridge, across the Tay, in the same way. So here is my sequel.

The Tay Bridge carries the East Coast Mainline railway track from the village of Wormit on the south coast of the Firth of Tay to Dundee city on the north coast. The bridge itself is two miles long and lies to the west of the modern Tay Road Bridge. While the vast length of the Tay Bridge is nowhere near as iconic as the enormous Forth Bridge, it does appear in comics and magazines. However most of those same publications are not about the Tay Bridge that we see today, but about the first Tay Bridge.

The Tay Bridge carries the East Coast Mainline railway track from the village of Wormit on the south coast of the Firth of Tay to Dundee city on the north coast. The bridge itself is two miles long and lies to the west of the modern Tay Road Bridge. While the vast length of the Tay Bridge is nowhere near as iconic as the enormous Forth Bridge, it does appear in comics and magazines. However most of those same publications are not about the Tay Bridge that we see today, but about the first Tay Bridge. The original Tay Bridge was completed in 1877 and at the time was the longest bridge in the world. Trains travelling over it were reputed to break the bridge’s speed limit in an attempt to beat the Tay ferries to the shore, although perhaps not as blatantly as DCT and IPC artist Keith Robson shows in the above illustration from the delightful Time Tram Dundee, a ‘Horrible History’ style book devoted to the history of the city. The bridge itself was a public marvel with even Queen Victoria making an official crossing of it, yet it is said that the men who worked on it after it was completed would regularly loose tools into the water below because of the movement of the bridge when trains passed over it, as shown here by artist Andrew Howat in Look and Learn 916, 11 August 1979.

The original Tay Bridge was completed in 1877 and at the time was the longest bridge in the world. Trains travelling over it were reputed to break the bridge’s speed limit in an attempt to beat the Tay ferries to the shore, although perhaps not as blatantly as DCT and IPC artist Keith Robson shows in the above illustration from the delightful Time Tram Dundee, a ‘Horrible History’ style book devoted to the history of the city. The bridge itself was a public marvel with even Queen Victoria making an official crossing of it, yet it is said that the men who worked on it after it was completed would regularly loose tools into the water below because of the movement of the bridge when trains passed over it, as shown here by artist Andrew Howat in Look and Learn 916, 11 August 1979. However this first bridge would only last for 19 months. On Sunday 28 December 1879 there was a severe storm with winds blowing to Storm Force 10. The 5:20pm train from Burntisland in Fife to Dundee passed the bridge’s southern signal box and onto the single track bridge at 7:13pm. The train should have made the crossing in six minutes but 7:19pm came and went and the train never appeared at the north end.

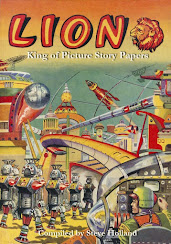

However this first bridge would only last for 19 months. On Sunday 28 December 1879 there was a severe storm with winds blowing to Storm Force 10. The 5:20pm train from Burntisland in Fife to Dundee passed the bridge’s southern signal box and onto the single track bridge at 7:13pm. The train should have made the crossing in six minutes but 7:19pm came and went and the train never appeared at the north end. We now know that the centre section of the bridge, known as the High Girders, was not designed strongly enough to withstand such a storm and on that fateful night it collapsed taking the train and all its 75 passengers and crew 88 feet into the river below. Yet the exact sequence of events remains open to speculation to this day. Had the section been weakened so much by the storm that it unexpected collapsed as the train went over it? Did the train derail and cause the weak structure to collapse? Indeed you can speculate yourself based on the facts at the Open University site about the disaster. The possibility also existed that the bridge section had collapsed before the train reached it and this scenario was shown in the factual story of the disaster in the 1972 Lion Annual, shown above, as well as in the aforementioned Look and Learn.

We now know that the centre section of the bridge, known as the High Girders, was not designed strongly enough to withstand such a storm and on that fateful night it collapsed taking the train and all its 75 passengers and crew 88 feet into the river below. Yet the exact sequence of events remains open to speculation to this day. Had the section been weakened so much by the storm that it unexpected collapsed as the train went over it? Did the train derail and cause the weak structure to collapse? Indeed you can speculate yourself based on the facts at the Open University site about the disaster. The possibility also existed that the bridge section had collapsed before the train reached it and this scenario was shown in the factual story of the disaster in the 1972 Lion Annual, shown above, as well as in the aforementioned Look and Learn. It was inevitable that the disaster would make the cover of Look and Learn. Issue 524 dated 29 January 1972 had this dramatic cover of Engine 224 taking its train and passengers to their doom.

It was inevitable that the disaster would make the cover of Look and Learn. Issue 524 dated 29 January 1972 had this dramatic cover of Engine 224 taking its train and passengers to their doom. The realisation of what had happened came fairly quickly. The signalmen at the southern end of the bridge could not contact the signal box on the north end and set out into that cold dark night along the bridge before being driven back by the storm. They saw what had happened only as the storm abated a little. As part of the Look and Learn 'This Made Headlines' series artist John Keay painted this image of the aftermath in Look and Learn issue 874, dated 14 October 1978.

The realisation of what had happened came fairly quickly. The signalmen at the southern end of the bridge could not contact the signal box on the north end and set out into that cold dark night along the bridge before being driven back by the storm. They saw what had happened only as the storm abated a little. As part of the Look and Learn 'This Made Headlines' series artist John Keay painted this image of the aftermath in Look and Learn issue 874, dated 14 October 1978. In fact the steam engine was actually recovered from the Tay, yet only 46 of the 75 bodies were ever found, the last almost four months after the tragedy. Engine 224 was refurbished and, ironically nicknamed The Diver, would continue to serve for some forty years as shown in 'The Little Engine That Had Two Lives' from Ranger 2 October 1965.

In fact the steam engine was actually recovered from the Tay, yet only 46 of the 75 bodies were ever found, the last almost four months after the tragedy. Engine 224 was refurbished and, ironically nicknamed The Diver, would continue to serve for some forty years as shown in 'The Little Engine That Had Two Lives' from Ranger 2 October 1965. All the above references have come from factual articles, indeed it would seem somewhat in bad taste to include such a tragedy in a fictional story for children, yet the Lion Annual for 1976 tackled the disaster with their own tragic character, Adam Eterno.

All the above references have come from factual articles, indeed it would seem somewhat in bad taste to include such a tragedy in a fictional story for children, yet the Lion Annual for 1976 tackled the disaster with their own tragic character, Adam Eterno.

In the six page story Adam is called back to Earth on the night of the disaster to transport a gold key to Dundee on the doomed train and so is on board when the accident occurs. Since our hero can only be killed by a golden weapon, he is able to survive the wreck and make his way to Dundee city to complete his task. It has to be said that the art by the Spanish Solano Lopez studio portrays Engine 224 rather more like an American locomotive that the British steam engine it actually was.

In the six page story Adam is called back to Earth on the night of the disaster to transport a gold key to Dundee on the doomed train and so is on board when the accident occurs. Since our hero can only be killed by a golden weapon, he is able to survive the wreck and make his way to Dundee city to complete his task. It has to be said that the art by the Spanish Solano Lopez studio portrays Engine 224 rather more like an American locomotive that the British steam engine it actually was. The current bridge was completed in July 1887 having taken four years to build and in its 120 year history has been considerably safer than it predecessor. It was featured on the wraparound cover (above) of the See New Worlds free comic created for the Six Cities Design Festival in 2007. Written by Chris Murray and featuring art by Lyall Bruce, Victoria Baker and Stuart David Fallon, this mix of manga-like figure work in sketchy Dundee backgrounds is set in a virtual reality Dundee of 2037 which is being menaced by a creeping destructive darkness.

The current bridge was completed in July 1887 having taken four years to build and in its 120 year history has been considerably safer than it predecessor. It was featured on the wraparound cover (above) of the See New Worlds free comic created for the Six Cities Design Festival in 2007. Written by Chris Murray and featuring art by Lyall Bruce, Victoria Baker and Stuart David Fallon, this mix of manga-like figure work in sketchy Dundee backgrounds is set in a virtual reality Dundee of 2037 which is being menaced by a creeping destructive darkness. Slightly more obvious is the cover of Look and Learn Issue 921, 15 September 1979, where an Intercity train painted by Graham Coton crosses the bridge as a modern counterpoint to the first passenger steam train.

Slightly more obvious is the cover of Look and Learn Issue 921, 15 September 1979, where an Intercity train painted by Graham Coton crosses the bridge as a modern counterpoint to the first passenger steam train. Today only the single row of caissons of the first bridge remain, rising out of the Tay just to the east of the current bridge, in silent memorial to the 75 lives lost in what remains one of the worst railway accidents in British history.

Today only the single row of caissons of the first bridge remain, rising out of the Tay just to the east of the current bridge, in silent memorial to the 75 lives lost in what remains one of the worst railway accidents in British history.

I remember reading the Adam Eterno story in the 1976 Lion annual and I'll admit, even at 11 years old but already a budding Scottish railway enthusiast, I found it infuriating that the locomotive, although a 4-4-0, was more like the ones used in the late 19th century American West instead of 1870s Scotland. Us boys of the 1970s weren't that naive. The locomotive has a cowcatcher, something that was added to American locomotives to protect against a collision with a buffalo. Maybe the artist thought Scottish locomotives needed them because of the possibility of being charged by Highland cattle.

ReplyDelete