I've been taking some holiday time away from Look and Learn... which means I've had my nose to the grindstone working on the 4-book Karl the Viking box set for DLC again. 17,000 words written and the end is in sight at last! For light relief I've also written the introduction to a collection of Franco Caprioli's 'The Legend of Beowulf' which is to be published in Italy. The strip originally appeared in Look and Learn in 1970.

On the work front -- because I'm still "at work" the moment I sit down in front of the computer whether I'm on holiday or not! -- the deal between Look and Learn and ROK Comics has just had its first results launched: the classic Robin Hood strips produced by Frank Bellamy for Swift are now available as downloads for your mobile phone. There's a press release about it here and you can see a preview here.

A few things I've been catching up on this evening...

* An alternate version of The Black Diamond Detective Agency, Eddie Campbell's recent graphic novel. The Forbidden Planet International blog has details of a pitch produced by James Sturm and Nick Bertozzi based on Campbell's 2003 unproduced movie screenplay. Bertozzi has posted a number pages at Act-i-vate.

* 'Andi Watson Goes Clubbing', interview with Andi Watson by Jennifer M. Contino (Comicon.com, 21 August). Link via Journalista.

* 'Ennis Shows His 'Streets' Smarts', interview with Garth Ennis by Brian Warmoth (Wizard Universe, 21 August). Link via Journalista.

* John Adcock has been posting some interesting material from the pages of 1935-vintage issues of the News of the World, including adverts for various other publications and a run of a strip based on humorous takes on news stories by an artist who signed himself Cosmos: here, here and here. He's also recently posted examples of work by cartoonists Tom Cottrell and Arthur Ferrier.

Wednesday, August 22, 2007

Tuesday, August 21, 2007

Gerald Biss

Edwin Gerald Jones Biss was born in Cambridge in 1876, the fourth son of Cecil Yates Biss, a Harley Street physician who was a pioneer of the open-air treatment of consumption. Educated at University College, Leys School, Cambridge, and Trinity Hall, Cambridge, matriculating in 1895. He was originally intended for the Bar but, like many other budding barristers, he drifted into journalism and found himself with a very successful career, particularly his articles on the relatively new sport of motoring. His articles appeared in The Strand, Tatler, Daily Mail and Evening Standard and he was the motoring correspondent for the Sunday Times, the Sketch

Edwin Gerald Jones Biss was born in Cambridge in 1876, the fourth son of Cecil Yates Biss, a Harley Street physician who was a pioneer of the open-air treatment of consumption. Educated at University College, Leys School, Cambridge, and Trinity Hall, Cambridge, matriculating in 1895. He was originally intended for the Bar but, like many other budding barristers, he drifted into journalism and found himself with a very successful career, particularly his articles on the relatively new sport of motoring. His articles appeared in The Strand, Tatler, Daily Mail and Evening Standard and he was the motoring correspondent for the Sunday Times, the Sketchand a special correspondent for Vanity Fair (New York). One of his most popular columns, 'Motor Dicta' concerned "odds and ends of automobilism" appeared in the Evening Standard and The Sketch.

An ardent student of criminology, he could boast a large collection of criminal books as well as some interesting relics. According to one brief biographical sketch. "He studies the subject thoroughly scientifically, both from the medical and legal point of view," attributing his success largely to the fact that he can never "play the fool with his public."

"I aim at making all my plots, however unusual, appear credible," he once said. "I wish my reader to think, 'Well, this might have occurred,' or 'This might have happened to me at any time.' I try to create and preserve the illusion of probability and I frequently draw on life for my plots. The main idea in Branded -- one of the five novels I have written -- is based upon two famous criminal cases that thrilled the world a few years ago."

Biss was a popular writer of the feuilleton, writing serial stories for many leading magazines. "Serial writing has now become a habit with me, and I am afraid I am incurable," he said.

His best known novel, The Door of the Unreal, was his only supernatural yarn. Published in 1919, it appeared long before Hollywood established many of the conventions that nowadays are associated with werewolves. The novel was noted by H. P. Lovecraft in his 'Supernatural Horror in Literature' as handling "quite dexterously the standard werewolf superstition." The story is still in print from at least two different publishers and is available as a PDF download here (part 1), here (part 2) and here (part 3).

Physically large, Gerald Biss died suddenly at the age of 46, collapsing from a heart attack on 15 April 1922 whilst visiting a friend, A. E. Manning Foster, at his flat in Davies Street, Berkeley Square. Biss married Sarah Ann Coutts Allan (1878?-1952) at East Preston, Sussex, in 1905, and had a son, solicitor Godfrey Charles D'Arcy Biss (1909-1989) and a daughter, Couttie Margaret Janet Biss (1907-1988).

Of 'Gerry' Biss, a correspondent to The Times said, "It is seldom given to any man to have so many intimate friends, so many acquaintances who, in all walks of life without, perhaps, knowing him intimately, nevertheless, instinctively felt real, deep affection for this most jovial and kind-hearted of men. Gerry Biss was the friend to all. A writer of remarkable distinction, a man who set 'people' above 'things', gifted with just that imagination and enthusiasm which made his articles, in whatever paper, in whatever style, shine out with an individuality all their own."

Novels

The Dupe. London, Greening & Co., 1907.

The White Rose Mystery. London, Greening & Co., 1907.

Branded. London, Greening & Co., 1908.

The House of Terror. London, Greening & Co., 1909.

The Fated Five. The tale of a tontine. London, Greening & Co., 1910.

The Door of the Unreal. London, Eveleigh Nash Co., 1919; New York, G. P. Putnam, 1920.

Non-fiction

Motor Dicta. London, Greening & Co., 1909.

Labels:

Author

Henry Rawle

Henry Rawle was an obscure British writer of short horror stories whose fame, if any, rests on the fact that it was once believed that Rawle was the pen-name of prolific British pulpt writer John Russell Fearn.

Many years ago I managed to establish that Rawle was a real person, a member of the South London Writers' Circle in around 1947 and a contributor to their journal, Streete Corner, edited by Alan M. Streete, who was living at 13 Longton Avenue, Sydenham, S.E.26 in 1947/58 before disappearing from the London phone book.

It was this Writers' Circle that eventually led to finding Rawle. In August 1948, the Sydenham meeting was attended by Frank Tilsley, whose Champion Road had just been published. Tilsley's talk on how he came to write the novel was accompanied by reading of manuscripts by members, amongst them Henry Rawle's MS "Bright is the Morning". A brief newspaper report of the event mentioned that Rawle was an "accomplished fiction writer ... of Forest Hill."

Armed with this clue, it was possible to identify our author as Harry Walter Rawle, born in Greenwich, London, in 1915, the son of Francis William Rawle (1869-1929) and his wife, Mary Abigail Rawle (1869-1946). Shortly before Harry's birth, the 1911 census records his parents as living in Treherbert Rhondda, Glamorganshire, where his father worked as a colliery labourer (above ground) at the mines.

Francis had previously served in the Royal Horse Artillery before joining the Kent Artillery Reserve in 1898, serving abroad as a gunner in 1899-1902. He then worked as a labourer on the London docks. In 1914, he again joined up as a gunner in the Royal Horse & Field Artillery but was discharged after only 101 days in January 1915 on medical grounds.

He was married to Mary Abigail Scott in Pontypridd, Glamorganshire, in 1914, although they had been living together since possibly the late 1880s (claiming to have been married for 14 years [i.e. c.1897] in the 1911 census), and had two daughters: Nellie, born 4 August 1889, and Ethel, born in 1893. Both daughters emigrated, Nellie to Canada (where she died in 1928) and Ethel to Australia (where she died in 1981).

Two sons, Francis William George Arthur Rawle and James Rawle were born in Kennington, Kent, 8 October 1904 and Norwich, Norfolk, c.1905 respectively.

The family were almost certainly badly off, with James admitted to the Poor Law Hospital in 1916, at the age of 11, although why and whether he survived is unknown.

Harry, born in 1915, was living with his incapacitated mother, at 123 Keedonwood Road, Downham, Lewisham, in n 1937-39. He married in 1940 to Dorothy Susan Weaver and the two lived at 65 St. German's Road, Forest Hill, from at least 1945. Dorothy was born on 9 March 1917 and, in 1939, was living with her mother, Ada M. Weaver (1883-1966), and sister Ena D. Weaver (1913- ; later Reeves).

Harry and Dorothy lived together at the same address until 1953 when Rawle, describing his occupation as "engineer", left England for New Zealand, via Melbourne, Australia, aboard the R.M.S. Orion. He then lived in New Zealand, working variously as an engineer, fitter and toolmaker at No.3 Camp, Mangakino [1954], 4 Waione Road, Atiamuri [1957], 50 Union Street, Waihi [1963/81].

Harry Walter Rawles died on 26 August 1995 and was cremated at Hamilton Park Cemetery, Waikato. He was predeceased by Dorothy Susan Rawle, who died on 15 May 1987.

Rawle's stories continued to appear in the UK after his departure for New Zealand, although later appearances were almost certainly sold to Gerald Swan in the late 1940s/early 1950s, as he tended to build up stocks of stories. It is also worth noting that the odd pen-name Henry Retlaw is derived from Harry's middle name spelled backwards.

There are still one or two things that need tidying up about Harry's family tree (for instance, why was his mother's maiden name given as Roffey?), but for now, we'll just say that, for the most part, the mystery is solved.

Short Stories

Revanoff's Fantasia (Tales of Ghosts and Haunted Houses [Master Thriller 32], Dec 1939)

The Chained Terror (as by Henry Retlaw; Weird Story Magazine 1, Aug 1940)

In Alien Valleys (Weird Shorts, 1944)

The Bride of Yum-Chac (Occult, Sep 1945)

Flashback (Occult Shorts 2, Feb 1946)

Gruenaldo (as by Harry Rawle; Weird Story Magazine 1, 1946)

The Intruder (Weird & Occult Miscellany, Apr 1949)

Fiorello (New Acorn 1, Jun/Jul 1949)

Dr Gabrielle's Chair (Space Fact & Fiction 2, Apr 1954)

The Voice of Amalzzar (Weird & Occult Library 2, Sum 1960)

Silvester's Oasis (Weird & Occult Library 3, Aut 1960)

Many years ago I managed to establish that Rawle was a real person, a member of the South London Writers' Circle in around 1947 and a contributor to their journal, Streete Corner, edited by Alan M. Streete, who was living at 13 Longton Avenue, Sydenham, S.E.26 in 1947/58 before disappearing from the London phone book.

It was this Writers' Circle that eventually led to finding Rawle. In August 1948, the Sydenham meeting was attended by Frank Tilsley, whose Champion Road had just been published. Tilsley's talk on how he came to write the novel was accompanied by reading of manuscripts by members, amongst them Henry Rawle's MS "Bright is the Morning". A brief newspaper report of the event mentioned that Rawle was an "accomplished fiction writer ... of Forest Hill."

Armed with this clue, it was possible to identify our author as Harry Walter Rawle, born in Greenwich, London, in 1915, the son of Francis William Rawle (1869-1929) and his wife, Mary Abigail Rawle (1869-1946). Shortly before Harry's birth, the 1911 census records his parents as living in Treherbert Rhondda, Glamorganshire, where his father worked as a colliery labourer (above ground) at the mines.

Francis had previously served in the Royal Horse Artillery before joining the Kent Artillery Reserve in 1898, serving abroad as a gunner in 1899-1902. He then worked as a labourer on the London docks. In 1914, he again joined up as a gunner in the Royal Horse & Field Artillery but was discharged after only 101 days in January 1915 on medical grounds.

He was married to Mary Abigail Scott in Pontypridd, Glamorganshire, in 1914, although they had been living together since possibly the late 1880s (claiming to have been married for 14 years [i.e. c.1897] in the 1911 census), and had two daughters: Nellie, born 4 August 1889, and Ethel, born in 1893. Both daughters emigrated, Nellie to Canada (where she died in 1928) and Ethel to Australia (where she died in 1981).

Two sons, Francis William George Arthur Rawle and James Rawle were born in Kennington, Kent, 8 October 1904 and Norwich, Norfolk, c.1905 respectively.

The family were almost certainly badly off, with James admitted to the Poor Law Hospital in 1916, at the age of 11, although why and whether he survived is unknown.

Harry, born in 1915, was living with his incapacitated mother, at 123 Keedonwood Road, Downham, Lewisham, in n 1937-39. He married in 1940 to Dorothy Susan Weaver and the two lived at 65 St. German's Road, Forest Hill, from at least 1945. Dorothy was born on 9 March 1917 and, in 1939, was living with her mother, Ada M. Weaver (1883-1966), and sister Ena D. Weaver (1913- ; later Reeves).

Harry and Dorothy lived together at the same address until 1953 when Rawle, describing his occupation as "engineer", left England for New Zealand, via Melbourne, Australia, aboard the R.M.S. Orion. He then lived in New Zealand, working variously as an engineer, fitter and toolmaker at No.3 Camp, Mangakino [1954], 4 Waione Road, Atiamuri [1957], 50 Union Street, Waihi [1963/81].

Harry Walter Rawles died on 26 August 1995 and was cremated at Hamilton Park Cemetery, Waikato. He was predeceased by Dorothy Susan Rawle, who died on 15 May 1987.

Rawle's stories continued to appear in the UK after his departure for New Zealand, although later appearances were almost certainly sold to Gerald Swan in the late 1940s/early 1950s, as he tended to build up stocks of stories. It is also worth noting that the odd pen-name Henry Retlaw is derived from Harry's middle name spelled backwards.

There are still one or two things that need tidying up about Harry's family tree (for instance, why was his mother's maiden name given as Roffey?), but for now, we'll just say that, for the most part, the mystery is solved.

Short Stories

Revanoff's Fantasia (Tales of Ghosts and Haunted Houses [Master Thriller 32], Dec 1939)

The Chained Terror (as by Henry Retlaw; Weird Story Magazine 1, Aug 1940)

In Alien Valleys (Weird Shorts, 1944)

The Bride of Yum-Chac (Occult, Sep 1945)

Flashback (Occult Shorts 2, Feb 1946)

Gruenaldo (as by Harry Rawle; Weird Story Magazine 1, 1946)

The Intruder (Weird & Occult Miscellany, Apr 1949)

Fiorello (New Acorn 1, Jun/Jul 1949)

Dr Gabrielle's Chair (Space Fact & Fiction 2, Apr 1954)

The Voice of Amalzzar (Weird & Occult Library 2, Sum 1960)

Silvester's Oasis (Weird & Occult Library 3, Aut 1960)

Labels:

Author

Monday, August 20, 2007

W. Holt-White

I had the good fortune recently to stumble upon a series of old (1913-14) paperbacks which contained 'bijou biographies' of some of the series' authors along with photographs. Over the next few days I'm hoping to share some of them with you as many of the books were by big names of their day who have since slipped into obscurity.

William Edward Bradden Holt-White was born in Hanwell, Middlesex, on 22 September 1878, the son of William (an architect) and his second wife Jane Bateson White (nee Cooke) who had married a year before. William had previously been married to Ellen H. White.

William Edward Bradden Holt-White was born in Hanwell, Middlesex, on 22 September 1878, the son of William (an architect) and his second wife Jane Bateson White (nee Cooke) who had married a year before. William had previously been married to Ellen H. White.

Holt would appear to have been a family name also, I suspect, given to William's younger sisters Gertrude Florence H. H. White (1879- ) and Helena Elizabeth H. H. White (1881- ).

William was originally intended for the Church, something of a family custom as three of his immediate relatives were bishops. His career took a different path and he was in turn a footballer, boxer, longshoreman and special correspondent around half the world. Holt-White wrote that "Constant change and a spirit of adventure are the main constituents of happiness. Adventures are to the adventurous. Every time I walk upstairs I hope that I may meet an angel at the top and every time I walk downstairs I think how jolly it would be to meet a burglar at the bottom. I have been nearly all over the world, but I find London the finest place of adventure. Every time I blithely mount a motor-'bus I do so no merely to get from one place to another but with the sence that I am meeting with adventure at the corner."

"It was my journalistic experience which gave me this idea. The life of the modern special correspondent is one long series of adventures. I have ridden with the North-West Mounted Police across the prairie, enjoyed the hospitality of princes and potentates and hunted with Scotland Yard men on many a murderous trail. And it comes in handy. Truth is stranger than fiction and were it not so there would be no fiction so far as I am concerned."

Whilst in his twenties, Holt-White began writing novels which have become popular among collectors of early science fiction. His first novel, The Earthquake. A romance of London in 1907 was inspired by the earthquake in San Francisco. "I simply transferred the earthquake to London and founded a novel on that."

The Man Who Stole the Earth was a Ruritanian novel of politics and romance inspired by "the first Zeppelin scare some years ago" and was responsible for "a spate of novels about future air wars" (Michael Paris, 'Fear of Flying: The Fiction of War 1886-1916'), although contemporary critics were not always complimentary of the story line, The New Age Supplement calling it "a crack-brained story of a young man whose author would have us believe was a general benefactor of humanity. By means of bombs dropped from an airship, this hero succeeds in gaining possession of Balkania, wherever that may be." The love-lorn inventor hero of the story "bombs most of Europe into submission in his drive to wed the daughter of the King of Balkania, forcing the world, en passant, into a state of peace" (John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction).

His other novels include Helen of All Time ("rather remarkably compresses into one volume an advance airship and the reincarnation of Helen of Troy", Clute); The Man Who Dreamed Right("movingly depicts an innocent man whose dreams predict the future and who is destroyed at the hands of the world's rulers (including Teddy Roosevelt), all desperate to corner his power", Clute); The World Stood Still, inspired by the 'Money Trust' which created something of a sensation in the United States ("not entirely plausibly describes the catastrophic effect on the world when its financiers go on strike", Clute; "Thriller of high finance and intrigue in which the four wealthiest men in America and Europe (who effectively control the world) decide to retire and hand the reins over to two young reprobates, causing world-wide chaos", George Locke, review); and The Woman Who Saved the World ("concerns near-future terrorism", Clute).

Holt-White's books also included biographies of Edward VII and Theodore Roosevelt.

At the age of 33, he was the editor of a London daily newspaper but forsook the editorial chair for advertising shortly before the beginning of the Great War. In 1914 he is said to have been a correspondent in Berlin.

Holt-White was married to Patricia Holt-White (in 1903) and as of 1915 was living in River Dup, Twickenham.

The BFI's Film and TV Database reveals something of his later life. In December 1915, Holt-White joined the Canadian War Records Office (some of his experiences were used in his final novel, The Super-Spy) and subsequently became the editor of Beaverbrook's paper for troops of the Canadian Overseas Expeditionary Force, the Canadian Daily Record. By July 1917 he was head of the Editorial Department at the War Office Official Topical Budget, supervising the production of newsreels for the Ministry of Information about actions during the war. He also remained in charge of publicity for the Canadian War Records Office.

Holt-White was made an honorary Lieutenant, then Captain, retaining his captaincy in peacetime. Unable to return to journalism, he remained with the Topical Film Company after 1918, working in much the same capacity as he had during the war, although now under William Jeapes' direction, whereas previously Jeapes had answered to him. Officially he was head of the editorial department, with news editor Charles Heath working under him. According to the BFI's biographical database, Holt-White "Must be considered the person most responsible for the high quality of much of Topical's output at this time." It would appear that Holt-White had left the company by 1926.

He died in Eastry, Kent, in late 1937, aged 59.

Novels

The Earthquake. A romance of London in 1907. London, E. Grant Richards, 1906.

The Man Who Stole the Earth. London, T. Fisher Unwin, 1909.

Helen of All Time. London, T. Fisher Unwin, 1910.

The Man Who Dreamed Right. London, Everett & Co., 1910.

The Prime Minister's Secret. London, T. Fisher Unwin, 1910; as The Crime Club, New York, Macaulay Co., 1910.

The World Stood Still. London, Everett & Co., 1912.

The Woman Who Saved the World. London, Everett & Co., 1914.

The Super-Spy. London, Andrew Melrose, 1916.

Non-fiction

The People's King. A short life of Edward VII. London, Eveleigh Nash, 1910.

Theodore Roosevelt. London, Andrew Melrose, 1910.

William Edward Bradden Holt-White was born in Hanwell, Middlesex, on 22 September 1878, the son of William (an architect) and his second wife Jane Bateson White (nee Cooke) who had married a year before. William had previously been married to Ellen H. White.

William Edward Bradden Holt-White was born in Hanwell, Middlesex, on 22 September 1878, the son of William (an architect) and his second wife Jane Bateson White (nee Cooke) who had married a year before. William had previously been married to Ellen H. White.Holt would appear to have been a family name also, I suspect, given to William's younger sisters Gertrude Florence H. H. White (1879- ) and Helena Elizabeth H. H. White (1881- ).

William was originally intended for the Church, something of a family custom as three of his immediate relatives were bishops. His career took a different path and he was in turn a footballer, boxer, longshoreman and special correspondent around half the world. Holt-White wrote that "Constant change and a spirit of adventure are the main constituents of happiness. Adventures are to the adventurous. Every time I walk upstairs I hope that I may meet an angel at the top and every time I walk downstairs I think how jolly it would be to meet a burglar at the bottom. I have been nearly all over the world, but I find London the finest place of adventure. Every time I blithely mount a motor-'bus I do so no merely to get from one place to another but with the sence that I am meeting with adventure at the corner."

"It was my journalistic experience which gave me this idea. The life of the modern special correspondent is one long series of adventures. I have ridden with the North-West Mounted Police across the prairie, enjoyed the hospitality of princes and potentates and hunted with Scotland Yard men on many a murderous trail. And it comes in handy. Truth is stranger than fiction and were it not so there would be no fiction so far as I am concerned."

Whilst in his twenties, Holt-White began writing novels which have become popular among collectors of early science fiction. His first novel, The Earthquake. A romance of London in 1907 was inspired by the earthquake in San Francisco. "I simply transferred the earthquake to London and founded a novel on that."

The Man Who Stole the Earth was a Ruritanian novel of politics and romance inspired by "the first Zeppelin scare some years ago" and was responsible for "a spate of novels about future air wars" (Michael Paris, 'Fear of Flying: The Fiction of War 1886-1916'), although contemporary critics were not always complimentary of the story line, The New Age Supplement calling it "a crack-brained story of a young man whose author would have us believe was a general benefactor of humanity. By means of bombs dropped from an airship, this hero succeeds in gaining possession of Balkania, wherever that may be." The love-lorn inventor hero of the story "bombs most of Europe into submission in his drive to wed the daughter of the King of Balkania, forcing the world, en passant, into a state of peace" (John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction).

His other novels include Helen of All Time ("rather remarkably compresses into one volume an advance airship and the reincarnation of Helen of Troy", Clute); The Man Who Dreamed Right("movingly depicts an innocent man whose dreams predict the future and who is destroyed at the hands of the world's rulers (including Teddy Roosevelt), all desperate to corner his power", Clute); The World Stood Still, inspired by the 'Money Trust' which created something of a sensation in the United States ("not entirely plausibly describes the catastrophic effect on the world when its financiers go on strike", Clute; "Thriller of high finance and intrigue in which the four wealthiest men in America and Europe (who effectively control the world) decide to retire and hand the reins over to two young reprobates, causing world-wide chaos", George Locke, review); and The Woman Who Saved the World ("concerns near-future terrorism", Clute).

Holt-White's books also included biographies of Edward VII and Theodore Roosevelt.

At the age of 33, he was the editor of a London daily newspaper but forsook the editorial chair for advertising shortly before the beginning of the Great War. In 1914 he is said to have been a correspondent in Berlin.

Holt-White was married to Patricia Holt-White (in 1903) and as of 1915 was living in River Dup, Twickenham.

The BFI's Film and TV Database reveals something of his later life. In December 1915, Holt-White joined the Canadian War Records Office (some of his experiences were used in his final novel, The Super-Spy) and subsequently became the editor of Beaverbrook's paper for troops of the Canadian Overseas Expeditionary Force, the Canadian Daily Record. By July 1917 he was head of the Editorial Department at the War Office Official Topical Budget, supervising the production of newsreels for the Ministry of Information about actions during the war. He also remained in charge of publicity for the Canadian War Records Office.

Holt-White was made an honorary Lieutenant, then Captain, retaining his captaincy in peacetime. Unable to return to journalism, he remained with the Topical Film Company after 1918, working in much the same capacity as he had during the war, although now under William Jeapes' direction, whereas previously Jeapes had answered to him. Officially he was head of the editorial department, with news editor Charles Heath working under him. According to the BFI's biographical database, Holt-White "Must be considered the person most responsible for the high quality of much of Topical's output at this time." It would appear that Holt-White had left the company by 1926.

He died in Eastry, Kent, in late 1937, aged 59.

Novels

The Earthquake. A romance of London in 1907. London, E. Grant Richards, 1906.

The Man Who Stole the Earth. London, T. Fisher Unwin, 1909.

Helen of All Time. London, T. Fisher Unwin, 1910.

The Man Who Dreamed Right. London, Everett & Co., 1910.

The Prime Minister's Secret. London, T. Fisher Unwin, 1910; as The Crime Club, New York, Macaulay Co., 1910.

The World Stood Still. London, Everett & Co., 1912.

The Woman Who Saved the World. London, Everett & Co., 1914.

The Super-Spy. London, Andrew Melrose, 1916.

Non-fiction

The People's King. A short life of Edward VII. London, Eveleigh Nash, 1910.

Theodore Roosevelt. London, Andrew Melrose, 1910.

Labels:

Author

Sunday, August 19, 2007

Alberto Saichann

One of unknown soldiers of Starblazer was Argentinean artist Alberto Saichann. He was one of a number of artists in the early issues whose artwork stood out: Enrique Alcatena is the obvious example since his work continued to appear regularly throughout the whole series -- meaning that more people are aware of his work than that of some of the more irregular contributors.

One of unknown soldiers of Starblazer was Argentinean artist Alberto Saichann. He was one of a number of artists in the early issues whose artwork stood out: Enrique Alcatena is the obvious example since his work continued to appear regularly throughout the whole series -- meaning that more people are aware of his work than that of some of the more irregular contributors. Alberto Saichann's first Starblazer was no. 25, 'Galactic Shootout', a story of space pirates which, frankly, got better artwork than the story deserved. Saichann was back in issue 42 for 'The Immortals' and no. 50 'Moonsplitter', the latter introducing Ray Aspden's Hadron Halley of the Fi-Sci (Fighting Scientists) unit of especially chosen scientists able to develop new weapons on the fly.

Alberto Saichann's first Starblazer was no. 25, 'Galactic Shootout', a story of space pirates which, frankly, got better artwork than the story deserved. Saichann was back in issue 42 for 'The Immortals' and no. 50 'Moonsplitter', the latter introducing Ray Aspden's Hadron Halley of the Fi-Sci (Fighting Scientists) unit of especially chosen scientists able to develop new weapons on the fly.Saichann contributed a further 10 stories, his output coming to an end with no. 156, 'The Sygma Warriors' in 1985.

For five years he contributed some of the best artwork the series was to see. Unfortunately, it was also some of the worst served by the printing as he often used a very thin line and there looks to be a lot of line drop-out on some of the printed copies. Despite this the quality did shine through. Saichann artwork is quite distinctive once you get to see it: his backgrounds were very detailed, whether cityscapes or the interiors of starships; he liked using Dutch angles; and, most obviously, liked psychedelic backgrounds of patterned letratone and random letratone letters and numbers were to be found throughout his work. There was just something about his work that grabbed my attention and made me look forward to seeing his work whenever it appeared.

For five years he contributed some of the best artwork the series was to see. Unfortunately, it was also some of the worst served by the printing as he often used a very thin line and there looks to be a lot of line drop-out on some of the printed copies. Despite this the quality did shine through. Saichann artwork is quite distinctive once you get to see it: his backgrounds were very detailed, whether cityscapes or the interiors of starships; he liked using Dutch angles; and, most obviously, liked psychedelic backgrounds of patterned letratone and random letratone letters and numbers were to be found throughout his work. There was just something about his work that grabbed my attention and made me look forward to seeing his work whenever it appeared. Saichann later contributed to Commando in 1988-91 before his work found an audience in America. He produced the 3-issue The Bronx for Eternity in 1991 and Rio Kid (1991-92) which lasted only 2 of the announced 3 issues. He had better luck with Continuity Comics, drawing Ms. Mystic, Armor and Megalith in 1993. He also drew the final (84th) issue of The 'Nam and Punisher Summer Special no.4 for Marvel.

Saichann later contributed to Commando in 1988-91 before his work found an audience in America. He produced the 3-issue The Bronx for Eternity in 1991 and Rio Kid (1991-92) which lasted only 2 of the announced 3 issues. He had better luck with Continuity Comics, drawing Ms. Mystic, Armor and Megalith in 1993. He also drew the final (84th) issue of The 'Nam and Punisher Summer Special no.4 for Marvel.Other US work has included The Gargoyles (1995), 'The Bronx II: The Actor' in Heavy Metal

(Jan 1996) and Superman: Our Worlds At War Secret Files & Origins (2001). In 2001-04, he inked stories for Looney Tunes for penciller Omar Aranda. His daughter, Pamela, is a tango dancer based in New York and co-founder of ReporTango magazine in 2002 where her father's work has occasionally appeared.

I had an opportunity to contact Alberto some time ago and he told me, with regards to his work for D C Thomson: "In those days I was working with a Spanish agent I'd known through a friend; there was no e-mail at that time. Everything was slow and we used post mail.

I had an opportunity to contact Alberto some time ago and he told me, with regards to his work for D C Thomson: "In those days I was working with a Spanish agent I'd known through a friend; there was no e-mail at that time. Everything was slow and we used post mail."Nowadays I'm basically drawing children's illustrations, painting about 'tango' and my country's tranditions, something I've wanted to do since I was young. I've not produced any comics for the last 8 years; apart from a Superman three years ago, my last work was five chapters of a Punisher for the USA."

It's a shame that Alberto has been lost to comics -- although comics' loss is children's illustration's gain, albeit in Argentina.

(* All the illustrations above come from various issues of Starblazer and are © D. C. Thomson.)

Labels:

Artist

Starblazer Adventures

In the third episode of my 'Starblazer Memories' columns below, I mentioned that Starblazer was set to return. Well, here's the story...

Starblazer has been licensed by British games publisher Cubicle 7 Entertainment, who also publish SLA Industries and Victoriana. Starblazer Adventures is a collection of detailed RPG settings based on elements from many of the 281 issues of Starblazer. The story elements are being pieced together by Chris Birch who told me recently "I'm hoping to make this RPG as accessible as possible non-gamers and borderline gamers. I've already organised playtests with non-gamers via dinner parties."

Starblazer has been licensed by British games publisher Cubicle 7 Entertainment, who also publish SLA Industries and Victoriana. Starblazer Adventures is a collection of detailed RPG settings based on elements from many of the 281 issues of Starblazer. The story elements are being pieced together by Chris Birch who told me recently "I'm hoping to make this RPG as accessible as possible non-gamers and borderline gamers. I've already organised playtests with non-gamers via dinner parties."

Chris say the games are based on "a fabulous story-telling focused game system called FATE." FATE, a tweaked version of the rules system that has been used recently for Evil Hat Productions' popular Spirit of the Century RPG.

Chris is incredibly enthusiastic about Starblazer and has been working hard to create a Starblazer Universe from the 24 dozen stories that appeared in Starblazer. "The core release will include three detailed settings based on the very best stories from Starblazer. It will also detail recurring characters, organisations, empires and aliens such as the Fi-Sci (the Fighting Scientists of Galac Squad), The Star Patrol, The Suicide Squad, The Planet Tamer, Cinnibar the barbarian warrior of Babalon and galactic cop Frank Carter to name just a few."

Chris has a background as a long-time fan of video and roleplaying games and set up a video games fashion label called Joystick Junkies which will be producing clothing designs based around Starblazer images. "There's so much more we can do if it goes well," Chris says. "I'm hoping we'll win over a lot of the old fans with the collections of stories and game play."

At the moment, you can see some of the work Chris has put in on his MySpace page. Eventually he will be be launching a website, starblazeradventures.com, but at the moment that address links through to his MySpace page... I'll be keeping an eye on the www address and will let you know when it goes live. Cubicle 7 has its own website, as do Joystick Junkies.

I'll bring you more news as it comes in.

Starblazer has been licensed by British games publisher Cubicle 7 Entertainment, who also publish SLA Industries and Victoriana. Starblazer Adventures is a collection of detailed RPG settings based on elements from many of the 281 issues of Starblazer. The story elements are being pieced together by Chris Birch who told me recently "I'm hoping to make this RPG as accessible as possible non-gamers and borderline gamers. I've already organised playtests with non-gamers via dinner parties."

Starblazer has been licensed by British games publisher Cubicle 7 Entertainment, who also publish SLA Industries and Victoriana. Starblazer Adventures is a collection of detailed RPG settings based on elements from many of the 281 issues of Starblazer. The story elements are being pieced together by Chris Birch who told me recently "I'm hoping to make this RPG as accessible as possible non-gamers and borderline gamers. I've already organised playtests with non-gamers via dinner parties."Chris say the games are based on "a fabulous story-telling focused game system called FATE." FATE, a tweaked version of the rules system that has been used recently for Evil Hat Productions' popular Spirit of the Century RPG.

Chris is incredibly enthusiastic about Starblazer and has been working hard to create a Starblazer Universe from the 24 dozen stories that appeared in Starblazer. "The core release will include three detailed settings based on the very best stories from Starblazer. It will also detail recurring characters, organisations, empires and aliens such as the Fi-Sci (the Fighting Scientists of Galac Squad), The Star Patrol, The Suicide Squad, The Planet Tamer, Cinnibar the barbarian warrior of Babalon and galactic cop Frank Carter to name just a few."

Chris has a background as a long-time fan of video and roleplaying games and set up a video games fashion label called Joystick Junkies which will be producing clothing designs based around Starblazer images. "There's so much more we can do if it goes well," Chris says. "I'm hoping we'll win over a lot of the old fans with the collections of stories and game play."

At the moment, you can see some of the work Chris has put in on his MySpace page. Eventually he will be be launching a website, starblazeradventures.com, but at the moment that address links through to his MySpace page... I'll be keeping an eye on the www address and will let you know when it goes live. Cubicle 7 has its own website, as do Joystick Junkies.

I'll bring you more news as it comes in.

Michael Hastings

Originally posted on 6 September 2006, this little piece on Michael Hastings has been the cause of some interesting research. Jacqueline Karp has been trying to trace information on Michael Hastings because he was her mother's first husband. Here's the original text which I will update at the end...

About the time I was asked to write the introduction to The Best of Girl some months ago, a few odd things converged. David Roach -- artist and general all-round comics' expert -- had sent me a pile of notes on Girl only a matter of weeks earlier and I'd been pondering (posh version of me going "huh?" and "You what?") over one of the credits he'd included. The scripts for 'Wendy and Jinx' -- the two inseparable chums of Manor School whose adventures graced the covers of Girl for a while -- were credited to Michael Hastings when the story first appeared in March 1952 and, after a few months, to Valerie Hastings. Could Valerie be the pseudonym of Michael, I wondered?

About the time I was asked to write the introduction to The Best of Girl some months ago, a few odd things converged. David Roach -- artist and general all-round comics' expert -- had sent me a pile of notes on Girl only a matter of weeks earlier and I'd been pondering (posh version of me going "huh?" and "You what?") over one of the credits he'd included. The scripts for 'Wendy and Jinx' -- the two inseparable chums of Manor School whose adventures graced the covers of Girl for a while -- were credited to Michael Hastings when the story first appeared in March 1952 and, after a few months, to Valerie Hastings. Could Valerie be the pseudonym of Michael, I wondered?

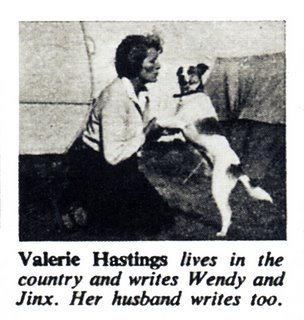

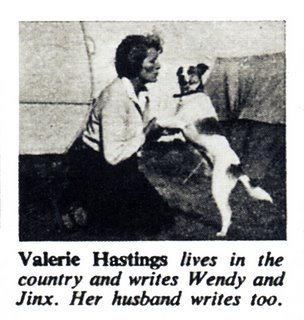

Soon after, I stumbled across a small picture of Valerie Hastings in the first anniversary issue of Girl which revealed that she "lives in the country and writes Wendy and Jinx. Her husband writes too."

Not much to go on, but it now looked like Michael and Valerie Hastings were husband and wife. Valerie had only a few books to her credit, starting with Wendy and Jinx and the Dutch Stamp Mystery, published as one of the 'Girl Novels' series by Hulton Press in 1956, followed a year later by a second. According to The Encyclopedia of Girls' School Stories "Both books combine a thriller-style main plot (jewel thieves in Dutch Stamp Mystery, Iron Curtain escapees and fraud in Missing Scientist) with a sub-plot set in school." Valerie Hastings wrote two other series, one featuring a character named Jo, the other starring Jill of Hazelmere School. Her last book appears to be Flood Tide, published by Harrap in 1967.

Not much to go on, but it now looked like Michael and Valerie Hastings were husband and wife. Valerie had only a few books to her credit, starting with Wendy and Jinx and the Dutch Stamp Mystery, published as one of the 'Girl Novels' series by Hulton Press in 1956, followed a year later by a second. According to The Encyclopedia of Girls' School Stories "Both books combine a thriller-style main plot (jewel thieves in Dutch Stamp Mystery, Iron Curtain escapees and fraud in Missing Scientist) with a sub-plot set in school." Valerie Hastings wrote two other series, one featuring a character named Jo, the other starring Jill of Hazelmere School. Her last book appears to be Flood Tide, published by Harrap in 1967.

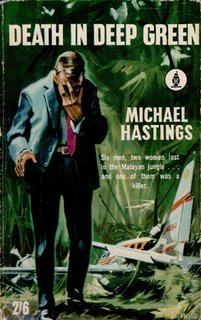

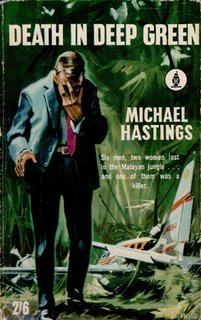

Michael Hastings, on the other hand, had at least 30 novels published, the last in 1980. Most were fast-moving action thrillers set in colourful locations: The Rising Sea (1962) is set on a South Seas island threatened by a tsunami and Death Across the Tamagash (1965) begins in a South American state wracked with revolution and counter revolution. You can get the feel of his novels from the titles alone: Death in Deep Green, The Coast of No Return, The Rising Sea, Dangerous Oasis, The Castle of Vengeance, Killer Road, etc.

Michael Hastings, on the other hand, had at least 30 novels published, the last in 1980. Most were fast-moving action thrillers set in colourful locations: The Rising Sea (1962) is set on a South Seas island threatened by a tsunami and Death Across the Tamagash (1965) begins in a South American state wracked with revolution and counter revolution. You can get the feel of his novels from the titles alone: Death in Deep Green, The Coast of No Return, The Rising Sea, Dangerous Oasis, The Castle of Vengeance, Killer Road, etc.

A brief biographical sketch of Hastings appears at The Evening News Short Story Index. Hastings was an irregular contributor, writing 51 stories for the paper between 1949 and 1978 and the sketch reveals Hastings to be...

"An adventure novelist and short story writer, Hastings was born in the Midlands but eventually settled on the South Coast after a spell in London. He served with the R.A.F. in the Middle East during the Second World War. Hastings travelled widely and drew on these experiences for backgrounds to his stories.With the help of John Herrington, another researcher of long-lost authors, I've managed to put together a few additional notes."

Michael Roy Hastings was born c.1907 and was living at St Leonards-on-Sea in the 1950s with his wife Valerie (b. 14 February 1902). According to a brief news report in the Hastings Observer (10 October 1959) which noted the publication of his sixth novel, "Mr. Hastings is also a writer of thrillers, but these are published under a pseudonym."

Huh? Unfortunately, we've yet to figure out what that pseudonym was. However, we do know that Hastings remained in St Leonards-on-Sea until the 1970s when he moved to nearby Bexhill-on-Sea where Valerie Hastings died in the autumn of 1975, aged 73. Michael Hastings continued to write until he also died, in 1980.

There are still a number of mysteries unresolved. There are at least two other authors named Michael Hastings (one born in 1938, another in 1958) and the three authors' works are sometimes credited to each other. However, there was one earlier thriller novel, They Killed a Spy (London, G. G. Harrap & Co., 1940) that might be by Michael Roy Hastings, twelve years before his next novel appeared.

There are still a number of mysteries unresolved. There are at least two other authors named Michael Hastings (one born in 1938, another in 1958) and the three authors' works are sometimes credited to each other. However, there was one earlier thriller novel, They Killed a Spy (London, G. G. Harrap & Co., 1940) that might be by Michael Roy Hastings, twelve years before his next novel appeared.

I'm also wondering whether Hastings might not have been the author of the first Girl cover strip, 'Kitty Hawke', who piloted a Tadcaster for her father, head of 'Hawke Air Charter, with an all-girl crew. I've never been able to find out who wrote these stories but Hastings is a possible suspect given his R.A.F. background and fondness of exotic locations for thrillers. Perhaps he was then asked to write a replacement strip and created Wendy and Jinx, later passing the scriptwriting chores on to his wife.

Pure speculation, of course, but not an outrageous idea. After all, if artist Ray Bailey could switch from Kitty to Wendy and Jinx why not the author?

But while I'm speculating, could the thriller pseudonym used by Hastings be Gabriel Hythe? Hythe is credited with three books from Macdonalds (Hastings' publisher), the first appearing in 1959 (same year as the newspaper report mentioned above); all three books were set in England, unlike Hastings' other novels (perhaps prompting the use of a pen-name) and Hythe, like Hastings, is the name of a town on the English south coast. Hythe is also credited with some stories in Argosy in 1967-69 and Hastings was contributing around the same time (1966-73); Hythe also contributed to the Evening News where both 'Hythe' and Hastings were appearing regularly until 1973, then had a five-year break before returning for one last story apiece in June 1978. Coincidence? I think not!

The question now is, how to prove it...

Update: 19 August 2007

One of the mysteries surrounding Michael Roy Hastings was that there was no record of his birth. If he had been born outside the U.K. that would have been understandable, but to be born in the Midlands and have no birth record would have been... not impossible, as even official records are misplaced and otherwise mucked up on occasion, but odd. We had quite a lot of fun trying to figure out whether Hastings was actually his real name or not. As it turns out, it was not the name he was born with.

Jacqueline's interest was concerned with her mother, Barbara. Born in Weymouth in 1916, Barbara Board had become one of the few female journalists working as a correspondent for British newspapers in the 1930s. Her experiences were revealed in two books, Newsgirl in Palestine (London, Michael Joseph, 1937) and Newsgirl in Egypt (London, Michael Joseph, 1938).

In 1940, she was living at the Belgrave Hotel in Holborn, London, at the same address as author Michael Roy Hastings. The two were married on 28 March 1940 so that Barbara could accompany her now husband when he was posted by the R.A.F. to the Middle East. Michael gave his occupation as 'author' on the marriage certificate which would seem to confirm that he is likely to have been the writer of the thriller They Killed a Spy (1940).

The marriage certificate was quite revealing as it gave the name of Hastings' father as Herbert William Higgins, a deceased accountant. Further digging has shown that Herbert Higgins was an accountant's clerk living in Birmingham in 1901, who had married Caroline Augusta Hart in 1899.

Michael and Barbara Hastings had only a brief marriage but I shall leave that story to Jacqueline to tell as she has been editing two unpublished manuscripts written by her mother for publication in January 2008 under the title Reporting From Palestine. Jacqueline is herself a poet and essayist and more information about the upcoming book and Jacqueline's own publications can be found on her website. You can pre-order Reporting From Palestine from amazon.co.uk.

Not all the mysteries surrounding Michael Hastings have been resolved. What was his birth name and why did he change his name from Higgins? Why can I find no record of his (second) marriage to Valerie Hastings despite an extensive search? His use of the pen-name Gabriel Hythe has since been accepted as being 99% certain -- that annoying and elusive 1% awaiting some kind of official confirmation from payment records or some other source. No doubt there will be more digging in future months.

Update: 9 September 2007

John Herrington has been able to resolve one of the outstanding queries: Michael Hastings was born Herbert Roy Higgins on 19 October 1907, his birth certificate confirming that he was the son of accountant's clerk Herbert W. Higgins (d. 1922, aged 50) and his wife Caroline A. Higgins (d. 1948) who lived at 711 Earlsbury Gardens, Handsworth, Staffordshire.

Update: 12 July 2008

Michael Hastings: the author that just keeps giving! Unbelievably, a completely separate enquiry has turned up some new and unexpected information on Hastings, a.k.a. Herbert Roy Higgins.

John Herrington (see above) posted a question about Alroy West, a pseudonymous writer of the 1930s, who had an entry in the 1935-36 Author's and Writer's Who's Who which gave an address in West Kirby, Cheshire. West wrote a series of thrillers for Wright & Brown between 1933 and 1937 before disappearing from the face of the earth.

As nobody seemed to have anything in the way of info., John checked out the address using the old electoral roles for West Kirby. Lo and behold, the person living at that address was... Herbert Roy Higgins!

The data for "Alroy West" included in Author's and Writer's mentioned that he was born in Handsworth, Staffs, which certainly ties in with what we know, and that he was educated at Bishop Vesey's, Sutton Coldfield. A check with the school confirms that Herbert was a pupil between 1 May 1919 and 1 December 1922. He is said to have been a writer on Egyptology and Eastern literature and a contributor to the Liverpool Weekly Post. He listed his interests as rowing, horse riding and chess.

John has also confirmed that the Michael Hastings who wrote the 1940 thriller They Killed a Spy is indeed "our" Michael Hastings, the link confirmed via correspondence he had with the agents A. P. Watts (via their archive which is held by the University of North Carolina).

We're creeping closer to having a better picture of Michael Hastings' output now. You have to wonder what will turn up in the future.

Novels as Michael Hastings

They Killed a Spy. London, G. G. Harrrap & Co., 1940.

Death in Deep Green. London, Methuen, 1952.

The Coast of No Return. London, Methuen, 1953.

The Digger of the Pit. London, Methuen, 1955.

The Man Who Came Back. London, Macdonald, 1957.

Twelve on Endurance. London, Macdonald, 1958.

An Hour-Glass to Eternity. London, Macdonald,1959.

The Voyage of the San Marcos. London, Macdonald, 1960.

The Citadel of Bats. London, Macdonald & Co., 1962.

The Rising Sea. London, Macdonald & Co., 1962.

The Port of Lost Cargoes. London, Macdonald & Co., 1963.

The Sands of Khali. London, Macdonald & Co., 1964.

Death Across the Tamagash. London, Macdonald & Co., 1965.

? Jim Blake, Archaeologist. London, Parrish, 1965.

The Green Silence. London, Macdonald & Co., 1966.

The Snake and the Arrow. London, Macdonald & Co., 1967.

Dangerous Oasis. London, Macdonald & Co., 1968.

The Killing in Black and White. London, Macdonald & Co., 1969.

Fire Mountain. London, Macdonald & Co., 1970.

The Castle of Vengeance. London, Macdonald & Co., 1971.

Killer Road. London, Macdonald & Co., 1972.

Tiger Reef. London, Macdonald & Co., 1973.

Dragon Island. London, Macdonald & Jane's, 1974.

Desert Convoy. London, Macdonald & Jane's, 1975.

River of Fate. London, Macdonad & Jane's, 1976.

The Trader of Skull Island. London, Macdonald & Jane's, 1977.

Satan's Bay. London, Macdonald & Jane's, 1978.

The Puma Quest. London, Macdonald & Jane's, 1979.

Veiled Isis. London, Macdonald & Jane's, 1980.

Novels as Gabriel Hythe

Death of a Puppet. London, Macdonald & Co., 1959; as by Michael Hastings, Skipton, N. Yorkshire, Dales Large Print, 2000.

Death of a Goblin. London, Macdonald & Co., 1960.

Death of a Scapegoat. London, Macdonald & Co., 1961.

Novels as Alroy West

The Crouching Men. London, Wright & Brown, 1933.

The Baying Hound. London, Wright & Brown, 1934.

Hate Island. London, Wright & Brown, 1934.

The Knife Terror. London, Wright & Brown, 1934.

The Man Who Didn’t Exist. London, Wright & Brown, 1935.

The Messengers of Death. London, Wright & Brown, 1935.

Stratosphere Express. London, Wright & Brown, 1936; abridged, Dublin, Mellifont Press, 1937.

The Beach of Skulls. London, Wright & Brown, 1937.

The Black Matador. London, Wright & Brown, 1937; abridged, Dublin, Mellifont Press, 1939.

(* 'Wendy and Jinx' © IPC Media Ltd.)

About the time I was asked to write the introduction to The Best of Girl some months ago, a few odd things converged. David Roach -- artist and general all-round comics' expert -- had sent me a pile of notes on Girl only a matter of weeks earlier and I'd been pondering (posh version of me going "huh?" and "You what?") over one of the credits he'd included. The scripts for 'Wendy and Jinx' -- the two inseparable chums of Manor School whose adventures graced the covers of Girl for a while -- were credited to Michael Hastings when the story first appeared in March 1952 and, after a few months, to Valerie Hastings. Could Valerie be the pseudonym of Michael, I wondered?

About the time I was asked to write the introduction to The Best of Girl some months ago, a few odd things converged. David Roach -- artist and general all-round comics' expert -- had sent me a pile of notes on Girl only a matter of weeks earlier and I'd been pondering (posh version of me going "huh?" and "You what?") over one of the credits he'd included. The scripts for 'Wendy and Jinx' -- the two inseparable chums of Manor School whose adventures graced the covers of Girl for a while -- were credited to Michael Hastings when the story first appeared in March 1952 and, after a few months, to Valerie Hastings. Could Valerie be the pseudonym of Michael, I wondered?Soon after, I stumbled across a small picture of Valerie Hastings in the first anniversary issue of Girl which revealed that she "lives in the country and writes Wendy and Jinx. Her husband writes too."

Not much to go on, but it now looked like Michael and Valerie Hastings were husband and wife. Valerie had only a few books to her credit, starting with Wendy and Jinx and the Dutch Stamp Mystery, published as one of the 'Girl Novels' series by Hulton Press in 1956, followed a year later by a second. According to The Encyclopedia of Girls' School Stories "Both books combine a thriller-style main plot (jewel thieves in Dutch Stamp Mystery, Iron Curtain escapees and fraud in Missing Scientist) with a sub-plot set in school." Valerie Hastings wrote two other series, one featuring a character named Jo, the other starring Jill of Hazelmere School. Her last book appears to be Flood Tide, published by Harrap in 1967.

Not much to go on, but it now looked like Michael and Valerie Hastings were husband and wife. Valerie had only a few books to her credit, starting with Wendy and Jinx and the Dutch Stamp Mystery, published as one of the 'Girl Novels' series by Hulton Press in 1956, followed a year later by a second. According to The Encyclopedia of Girls' School Stories "Both books combine a thriller-style main plot (jewel thieves in Dutch Stamp Mystery, Iron Curtain escapees and fraud in Missing Scientist) with a sub-plot set in school." Valerie Hastings wrote two other series, one featuring a character named Jo, the other starring Jill of Hazelmere School. Her last book appears to be Flood Tide, published by Harrap in 1967. Michael Hastings, on the other hand, had at least 30 novels published, the last in 1980. Most were fast-moving action thrillers set in colourful locations: The Rising Sea (1962) is set on a South Seas island threatened by a tsunami and Death Across the Tamagash (1965) begins in a South American state wracked with revolution and counter revolution. You can get the feel of his novels from the titles alone: Death in Deep Green, The Coast of No Return, The Rising Sea, Dangerous Oasis, The Castle of Vengeance, Killer Road, etc.

Michael Hastings, on the other hand, had at least 30 novels published, the last in 1980. Most were fast-moving action thrillers set in colourful locations: The Rising Sea (1962) is set on a South Seas island threatened by a tsunami and Death Across the Tamagash (1965) begins in a South American state wracked with revolution and counter revolution. You can get the feel of his novels from the titles alone: Death in Deep Green, The Coast of No Return, The Rising Sea, Dangerous Oasis, The Castle of Vengeance, Killer Road, etc.A brief biographical sketch of Hastings appears at The Evening News Short Story Index. Hastings was an irregular contributor, writing 51 stories for the paper between 1949 and 1978 and the sketch reveals Hastings to be...

"An adventure novelist and short story writer, Hastings was born in the Midlands but eventually settled on the South Coast after a spell in London. He served with the R.A.F. in the Middle East during the Second World War. Hastings travelled widely and drew on these experiences for backgrounds to his stories.With the help of John Herrington, another researcher of long-lost authors, I've managed to put together a few additional notes."

Michael Roy Hastings was born c.1907 and was living at St Leonards-on-Sea in the 1950s with his wife Valerie (b. 14 February 1902). According to a brief news report in the Hastings Observer (10 October 1959) which noted the publication of his sixth novel, "Mr. Hastings is also a writer of thrillers, but these are published under a pseudonym."

Huh? Unfortunately, we've yet to figure out what that pseudonym was. However, we do know that Hastings remained in St Leonards-on-Sea until the 1970s when he moved to nearby Bexhill-on-Sea where Valerie Hastings died in the autumn of 1975, aged 73. Michael Hastings continued to write until he also died, in 1980.

There are still a number of mysteries unresolved. There are at least two other authors named Michael Hastings (one born in 1938, another in 1958) and the three authors' works are sometimes credited to each other. However, there was one earlier thriller novel, They Killed a Spy (London, G. G. Harrap & Co., 1940) that might be by Michael Roy Hastings, twelve years before his next novel appeared.

There are still a number of mysteries unresolved. There are at least two other authors named Michael Hastings (one born in 1938, another in 1958) and the three authors' works are sometimes credited to each other. However, there was one earlier thriller novel, They Killed a Spy (London, G. G. Harrap & Co., 1940) that might be by Michael Roy Hastings, twelve years before his next novel appeared.I'm also wondering whether Hastings might not have been the author of the first Girl cover strip, 'Kitty Hawke', who piloted a Tadcaster for her father, head of 'Hawke Air Charter, with an all-girl crew. I've never been able to find out who wrote these stories but Hastings is a possible suspect given his R.A.F. background and fondness of exotic locations for thrillers. Perhaps he was then asked to write a replacement strip and created Wendy and Jinx, later passing the scriptwriting chores on to his wife.

Pure speculation, of course, but not an outrageous idea. After all, if artist Ray Bailey could switch from Kitty to Wendy and Jinx why not the author?

But while I'm speculating, could the thriller pseudonym used by Hastings be Gabriel Hythe? Hythe is credited with three books from Macdonalds (Hastings' publisher), the first appearing in 1959 (same year as the newspaper report mentioned above); all three books were set in England, unlike Hastings' other novels (perhaps prompting the use of a pen-name) and Hythe, like Hastings, is the name of a town on the English south coast. Hythe is also credited with some stories in Argosy in 1967-69 and Hastings was contributing around the same time (1966-73); Hythe also contributed to the Evening News where both 'Hythe' and Hastings were appearing regularly until 1973, then had a five-year break before returning for one last story apiece in June 1978. Coincidence? I think not!

The question now is, how to prove it...

Update: 19 August 2007

One of the mysteries surrounding Michael Roy Hastings was that there was no record of his birth. If he had been born outside the U.K. that would have been understandable, but to be born in the Midlands and have no birth record would have been... not impossible, as even official records are misplaced and otherwise mucked up on occasion, but odd. We had quite a lot of fun trying to figure out whether Hastings was actually his real name or not. As it turns out, it was not the name he was born with.

Jacqueline's interest was concerned with her mother, Barbara. Born in Weymouth in 1916, Barbara Board had become one of the few female journalists working as a correspondent for British newspapers in the 1930s. Her experiences were revealed in two books, Newsgirl in Palestine (London, Michael Joseph, 1937) and Newsgirl in Egypt (London, Michael Joseph, 1938).

In 1940, she was living at the Belgrave Hotel in Holborn, London, at the same address as author Michael Roy Hastings. The two were married on 28 March 1940 so that Barbara could accompany her now husband when he was posted by the R.A.F. to the Middle East. Michael gave his occupation as 'author' on the marriage certificate which would seem to confirm that he is likely to have been the writer of the thriller They Killed a Spy (1940).

The marriage certificate was quite revealing as it gave the name of Hastings' father as Herbert William Higgins, a deceased accountant. Further digging has shown that Herbert Higgins was an accountant's clerk living in Birmingham in 1901, who had married Caroline Augusta Hart in 1899.

Michael and Barbara Hastings had only a brief marriage but I shall leave that story to Jacqueline to tell as she has been editing two unpublished manuscripts written by her mother for publication in January 2008 under the title Reporting From Palestine. Jacqueline is herself a poet and essayist and more information about the upcoming book and Jacqueline's own publications can be found on her website. You can pre-order Reporting From Palestine from amazon.co.uk.

Not all the mysteries surrounding Michael Hastings have been resolved. What was his birth name and why did he change his name from Higgins? Why can I find no record of his (second) marriage to Valerie Hastings despite an extensive search? His use of the pen-name Gabriel Hythe has since been accepted as being 99% certain -- that annoying and elusive 1% awaiting some kind of official confirmation from payment records or some other source. No doubt there will be more digging in future months.

Update: 9 September 2007

John Herrington has been able to resolve one of the outstanding queries: Michael Hastings was born Herbert Roy Higgins on 19 October 1907, his birth certificate confirming that he was the son of accountant's clerk Herbert W. Higgins (d. 1922, aged 50) and his wife Caroline A. Higgins (d. 1948) who lived at 711 Earlsbury Gardens, Handsworth, Staffordshire.

Update: 12 July 2008

Michael Hastings: the author that just keeps giving! Unbelievably, a completely separate enquiry has turned up some new and unexpected information on Hastings, a.k.a. Herbert Roy Higgins.

John Herrington (see above) posted a question about Alroy West, a pseudonymous writer of the 1930s, who had an entry in the 1935-36 Author's and Writer's Who's Who which gave an address in West Kirby, Cheshire. West wrote a series of thrillers for Wright & Brown between 1933 and 1937 before disappearing from the face of the earth.

As nobody seemed to have anything in the way of info., John checked out the address using the old electoral roles for West Kirby. Lo and behold, the person living at that address was... Herbert Roy Higgins!

The data for "Alroy West" included in Author's and Writer's mentioned that he was born in Handsworth, Staffs, which certainly ties in with what we know, and that he was educated at Bishop Vesey's, Sutton Coldfield. A check with the school confirms that Herbert was a pupil between 1 May 1919 and 1 December 1922. He is said to have been a writer on Egyptology and Eastern literature and a contributor to the Liverpool Weekly Post. He listed his interests as rowing, horse riding and chess.

John has also confirmed that the Michael Hastings who wrote the 1940 thriller They Killed a Spy is indeed "our" Michael Hastings, the link confirmed via correspondence he had with the agents A. P. Watts (via their archive which is held by the University of North Carolina).

We're creeping closer to having a better picture of Michael Hastings' output now. You have to wonder what will turn up in the future.

Novels as Michael Hastings

They Killed a Spy. London, G. G. Harrrap & Co., 1940.

Death in Deep Green. London, Methuen, 1952.

The Coast of No Return. London, Methuen, 1953.

The Digger of the Pit. London, Methuen, 1955.

The Man Who Came Back. London, Macdonald, 1957.

Twelve on Endurance. London, Macdonald, 1958.

An Hour-Glass to Eternity. London, Macdonald,1959.

The Voyage of the San Marcos. London, Macdonald, 1960.

The Citadel of Bats. London, Macdonald & Co., 1962.

The Rising Sea. London, Macdonald & Co., 1962.

The Port of Lost Cargoes. London, Macdonald & Co., 1963.

The Sands of Khali. London, Macdonald & Co., 1964.

Death Across the Tamagash. London, Macdonald & Co., 1965.

? Jim Blake, Archaeologist. London, Parrish, 1965.

The Green Silence. London, Macdonald & Co., 1966.

The Snake and the Arrow. London, Macdonald & Co., 1967.

Dangerous Oasis. London, Macdonald & Co., 1968.

The Killing in Black and White. London, Macdonald & Co., 1969.

Fire Mountain. London, Macdonald & Co., 1970.

The Castle of Vengeance. London, Macdonald & Co., 1971.

Killer Road. London, Macdonald & Co., 1972.

Tiger Reef. London, Macdonald & Co., 1973.

Dragon Island. London, Macdonald & Jane's, 1974.

Desert Convoy. London, Macdonald & Jane's, 1975.

River of Fate. London, Macdonad & Jane's, 1976.

The Trader of Skull Island. London, Macdonald & Jane's, 1977.

Satan's Bay. London, Macdonald & Jane's, 1978.

The Puma Quest. London, Macdonald & Jane's, 1979.

Veiled Isis. London, Macdonald & Jane's, 1980.

Novels as Gabriel Hythe

Death of a Puppet. London, Macdonald & Co., 1959; as by Michael Hastings, Skipton, N. Yorkshire, Dales Large Print, 2000.

Death of a Goblin. London, Macdonald & Co., 1960.

Death of a Scapegoat. London, Macdonald & Co., 1961.

Novels as Alroy West

The Crouching Men. London, Wright & Brown, 1933.

The Baying Hound. London, Wright & Brown, 1934.

Hate Island. London, Wright & Brown, 1934.

The Knife Terror. London, Wright & Brown, 1934.

The Man Who Didn’t Exist. London, Wright & Brown, 1935.

The Messengers of Death. London, Wright & Brown, 1935.

Stratosphere Express. London, Wright & Brown, 1936; abridged, Dublin, Mellifont Press, 1937.

The Beach of Skulls. London, Wright & Brown, 1937.

The Black Matador. London, Wright & Brown, 1937; abridged, Dublin, Mellifont Press, 1939.

(* 'Wendy and Jinx' © IPC Media Ltd.)

Labels:

Author

Comic Clippings - August

It's coming up for Annuals season again so I'm wondering whether anyone out there has access to The Bookseller's best-sellers charts or UK sales data from Nielsen BookScan? Let me know off-list (my e-mail address is over there on the right) if you think you can help.

* Alan Grant and Cam Kennedy are producing a follow-up to their recent adaptation of Kidnapped. According to Mike Wade of The Times (17 August) they are currently working on another Robert Louis Stevenson classic, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyl and Mr Hyde.

* Chelsea football club is to be visited by Dennis the Menace. In 'Terry shares top billing with cartoon legend', Alyson Rudd reveals: "It used to be that the rich and famous knew they had made it when they appeared in latex form on Spitting Image. Today's barometer is cartoons and John Terry, the Chelsea captain, can relax; he has shared a strip with Dennis the Menace and was so flattered he gave The Beano an exclusive interview in return."

* Steve Flanagan pays tribute to Mytek the Mighty at Gad, Sir! Comics!

* Part 1 of an interview with Paul Gravett appears at The Daily Cross Hatch (link via Journalista).

* 'Comics aren't just read by nerds'. Christopher Taylor reviews Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean by Douglas Wolk (Daily Telegraph, 9 August).

* Alan Grant and Cam Kennedy are producing a follow-up to their recent adaptation of Kidnapped. According to Mike Wade of The Times (17 August) they are currently working on another Robert Louis Stevenson classic, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyl and Mr Hyde.

* Chelsea football club is to be visited by Dennis the Menace. In 'Terry shares top billing with cartoon legend', Alyson Rudd reveals: "It used to be that the rich and famous knew they had made it when they appeared in latex form on Spitting Image. Today's barometer is cartoons and John Terry, the Chelsea captain, can relax; he has shared a strip with Dennis the Menace and was so flattered he gave The Beano an exclusive interview in return."

* Steve Flanagan pays tribute to Mytek the Mighty at Gad, Sir! Comics!

* Part 1 of an interview with Paul Gravett appears at The Daily Cross Hatch (link via Journalista).

* 'Comics aren't just read by nerds'. Christopher Taylor reviews Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean by Douglas Wolk (Daily Telegraph, 9 August).

Labels:

Comics News

Friday, August 17, 2007

Phil Gascoine (1934-2007)

Phil Gascoine, who had a 45 year career in comics drawing for Britain, America and Europe, has died after a short illness.

Phil Gascoine, who had a 45 year career in comics drawing for Britain, America and Europe, has died after a short illness.Born on 8 June 1934, Phil left school at 15 and turned his interest illustration and artwork into a career by calling in at art studios along Fleet Street where he was able to obtain work as an office boy. His contacts with the various studios earned him his first freelance work. After doing his two years national service, he returned to work in a studio but found he was spending much of his time doing nothing. Finding an agent, he began freelancing artwork to Pearsons, drawing episodes of their Emergency Ward 10 pocket library, based on the TV series.

He sent samples of his work to D. C. Thomson, wrapping them in a piece of card on which he had drawn a young girl at an ice skating rink. Thomsons had just launched Bunty and were looking for artists for this new line in girls' comics. Phil spent most of the next fifteen years drawing for Bunty, School Friend, June and Jinty.

In the mid-1970s, he came to wider attention in Battle Picture Weekly, which began running credits for artists and writers in the wake of a similar move by 2000AD. Adopting a far grittier style than he had used in girls' stories, he drew various features ('Battle Badge of Bravery', Battle Honours', 'Unsung Heroes of War', etc.) and strips ('The Sarge', 'The Wilde Bunch', 'Sailor Small'). Around the same time he also drew football and boxing strips for Victor.

With the attention of the wider market, Gascoine began drawing strips for Marvel UK, including 'Blake's 7', 'Thundercats', 'Action Force', 'Adventures of the Galaxy Rangers' and 'The Real Ghostbusters', for five years, although retained his connection with Fleetway, for whom he drew 'News Team' (in Eagle) and various strips for Tammy. In 1985-86, Gascoine was also working for Look-In, drawing episodes of 'Robin of Sherwood' and 'Knight Rider'.

Gascoine was one of many artists tempted to work for DC Comics, producing The Unknown Soldier in 1988-89. He found regular work with Marvel UK during their American boom period (1992-94) when he was pencilling Knights of Pendragon, Motormouth and Genetix. During this period he also drew 'Darkhawk' for Marvel, the 4-issue Dreadlands for Epic, pencilled The Punisher: Die Hard in the Big Easy for DC and inked Tank Girl: Apocalypse, Egypt and Shade: The Changing Man for Vertigo.

In later years, with the market contracted, Gascoine still found work, drawing strips for lad's mag Loaded and the girls' comic Wendy, produced by D. C. Thomson for distribution abroad.

An interview with Gascoine, originally published in Eagle Flies Again in 2006, can be found at John Freeman's Down the Tubes site.

(* The illustration above was produced by Phil for the SSI and is © The Estate of Phil Gascoine.)

Wednesday, August 15, 2007

Starblazer memories

Today, Bear Alley is one year old. I've already talked about some of my experiences with fanzines so it seems apt that today's column should be about my experiences as a professional comic strip writer. Because, yes, I wrote two (count 'em) comic strips way back in the late 1980s. OK, so it's not quite the glittering career that some folks have had but at least I can say that, for two whole months, comic strips I had written were on the newsstands. And this, dear reader, is how it happened...

Today, Bear Alley is one year old. I've already talked about some of my experiences with fanzines so it seems apt that today's column should be about my experiences as a professional comic strip writer. Because, yes, I wrote two (count 'em) comic strips way back in the late 1980s. OK, so it's not quite the glittering career that some folks have had but at least I can say that, for two whole months, comic strips I had written were on the newsstands. And this, dear reader, is how it happened...I'm amazed at how many people remember Starblazer. It's now over fifteen years since the last issue appeared but the Starblazer pocket books appeared regular as clockwork throughout the 1980s at the rate of two new titles a month so I guess over the nearly twelve years it appeared a vast army of young science fiction fans, high on Star Wars or Battlestar Galactica, sought them out.

The series began with a single title in April 1979, 'The Omega Experiment' which had an excellent cover... it leapt out from amongst the Commando pocket libraries and I grabbed it with both hands. The artwork inside was a little less inspiring but I coughed up my 12 pence and read it on the bus home. I was about to celebrate my 17th birthday and science fiction was all I read at that time. I was frighteningly dedicated to the genre. When it came to choosing a subject for a school project, I chose science fiction magazines which began my first tentative steps as a digger at the coal face of what academics call "pulp culture". I don't want to turn this into a huge autobiographical sprawl (and I covered some of this yesterday) but it was luck that got me back into comics in the mid-1980s but my interest in research that made me stick with them.

In 1986 I was corresponding with an artist by the name of Tony O'Donnell and we put together an article about Starblazer for a fanzine called Fusion. Tony had been an occasional contributor to Starblazer since 1983 but was more regularly to be found in the pages of Buddy and Spike at that time (you can find out a lot more about Tony's early career via this excellent interview by Garen Ewing). Tony and I were both fans of an at-the-time unidentified South American artist who had been drawing stories for Starblazer since its early days whose name turned out to be Enrique Alcatena. A brilliant artist of science fiction and fantasy, Alcatena also turned his hand to some superbly drawn historical strips in Buddy and Victor, as well as a couple of SF epics like 'Sabor's Army' in Warlord. In 1988, 4-Winds published his graphic novel Moving Fortress which had originally appeared in the Argentinean magazine Skorpio, and, before long, he was inking Hawkworld for DC, his work championed in the US by Tim Truman.