HAROLD C. EARNSHAW

by

Robert J. Kirkpatrick

The artistic and illustrative work of Harold C. Earnshaw has been overlooked in favour of that of his wife, Mabel Lucie Attwell, who had a long and rewarding career as an illustrator and painter, specializing in cute and comic pictures of young children. Yet Earnshaw’s story is well-worth telling, especially because having established himself as a professional artist, he lost his right arm during the First World War, and quickly taught himself to draw and paint with his left, and was able to maintain his career for a further 20 years.

Earnshaw, the sixth of nine children, was born, on 19 April 1886 in Woodford, Essex, and baptised Harold Cecil Earnshaw on 3 October 1886. His father, Frederick (1842-1919) was a banker’s clerk from Yorkshire; his mother, Sophia (née Peak, 1850-1932), was a former dressmaker, and the daughter of a commercial traveller.

Harold was brought up in Leyton, Essex – at the time of the 1891 census the family, of eight children and two servants, was living in Whipps Cross Road. Ten years later, they were at Gresley House, Cambridge Road, Wanstead. Harold subsequently took up at a place at St. Martin’s School of Art, in Long Acre, central London, and lived for a while at 22 Greenhill Park, Harlesden. It was at St. Martin’s that he met fellow art student Mabel Lucie Attwell, born in Mile End, London, on 4 June 1879, the sixth child of Augustus Attwell, a butcher, and his wife Emily. She had previously studied at the Heatherley School of Fine Art, and had already been working professionally since the turn of the century.

They subsequently married on 4 June 1908 at Hendon Registry Office, and moved to a flat in Dulwich, south London. They went on to have three children: Marjorie Jean (born on 13 May 1909), Peter Max (born on 22 July 1911), and Brian Attwell (born on 24 August 1914). By early 1911, the family had moved to “Casita”, Downs Road, Coulsden, Surrey. After Peter’s birth, they moved to “Fairdene” in nearby Fairdene Road.

(For some reason, the family used different names to their given ones: Harold was known as Pat, Marjorie as Peggy, Peter as Max, and Brian as Bill).

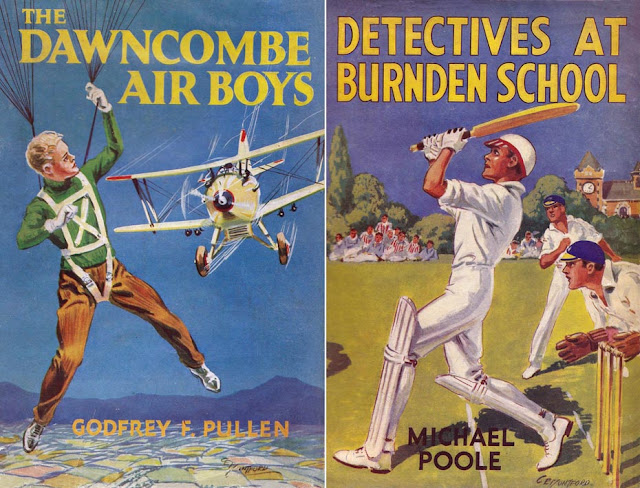

In the meantime, Earnshaw has established himself as a professional artist and illustrator. His earliest recorded work were colour plates in a re-issue of Talbot Baines Reed’s school story The Willoughby Captains, and in another school story, The Pretenders, by Meredith Fletcher, in 1907, both published by Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton. The following year, he joined the London Sketch Club, and began working with the publisher W. & R. Chambers, for whom he illustrated a number of school and historical stories. He also began working with Cassell & Co. providing illustrations for Cassell’s Magazine, although he only appears to have illustrated one book published by the firm, Ralph Simmonds’s For School and Country, published in 1991.

His illustrations soon began appearing in other periodicals, in particular Printers’ Pie and The Pall Mall Magazine, alongside The Boy’s Own Paper, The Red Magazine, The Yellow Magazine, The Graphic and The Bystander.

His style was, for the most part, rather idiosyncratic. He was capable of producing realistic illustrations, but in many of his colour and black & white plates, for boys’ books in particular, the characters looked far younger than they should have. It may well have been that, even before they were married, he had started adopting some of the characteristics found in illustrations by his future wife.

On 23 November 1915 Earnshaw enlisted in the Royal Sussex Regiment, after having earlier signed up with the Artists’ Rifles, part of the British Army’s volunteer reserve. As a Lance Corporal, he was serving in the Somme when, on 13 February 1917, his right arm was blown off at the elbow by an exploding shell. He was also injured in the back and one of his legs. Repatriated to England, he was treated in hospital in Stockport, where he taught himself to draw with his left hand. In an article by A.B. Cooper in The Captain (July 1918) Earnshaw explained:

I never thought my career as an artist was over. I think if I had lost both hands I should have immediately have started life as a barefoot artist. In fact, the moment I was able to hold a pen I wrote a letter to my wife, and then and in every subsequent letter – and I wrote many scores ¬ I made one or more humorous sketches, illustrating the text with myself, as a rule, the centre of the stage, whether at the base, on shipboard, or in hospital in Blighty, so that by the time my first commission came – a request for a drawing for Printers’ Pie, sent in ignorance of my wound, sent on by my wife more for fun than with any serious thought that I would then and there do the deed – I was quite prepared to face my work as usual.He was discharged from hospital on 17 July 1917, and less than two weeks later The Graphic published a full-page set of his sketches, “Down but not out: Leaves from a soldier’s hospital sketch-book.” As well as being clever little drawings, they were notable for their humour, an expression of Earnshaw’s optimism and complete lack of self-pity.

At his home, A.B. Cooper revealed that he had “several contraptions from Roehampton, where so many “handy” and “leggy” things are made for men who have lost limbs with the purpose of enabling them to “carry on.” These included a false right hand, a mahl stick holder (to provide support for the painting hand), and a device for holding a snooker cue – he played snooker, and golf, with fellow-artist Harry Rountree.

His work, which had continued to appear in books during the war, carried on as if nothing untoward had happened. He was used by a variety of publishers – W. & R. Chambers, Hodder & Stoughton, T. Nelson & Sons, Collins, the Oxford University Press, and C. Arthur Pearson. For a while he worked in collaboration with Elsie J. Oxenham, illustrating six of her books between 1914 and 1920. In the 1930s, he worked almost exclusively for Blackie & Son, largely on picture books for young children, a sharp contrast to his earlier work, when he had illustrated school, historical and adventure stories. He often worked in partnership with his wife, whose influence was clearly reflected in this later work.

He also continued contributing to magazines and periodicals, including The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, The Sketch (both of which published some of his illustrations in the autumn of 1917, following on from his wartime injury), The Sphere, Little Folks, The Tatler, The Illustrated London News and The Sheffield Weekly Telegraph. Between December 1928 and February 1931 his drew a comic strip, “The Pater” for The Daily Mirror. He also exhibited his paintings with the Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolours and at the Chenil Gallery in Chelsea, where he was also a member of the Chelsea Arts Club.

During the 1920s the Earnshaw family lived in Kensington, initially at 9 Roland Gardens then subsequently, from around 1926, at 32 Cranly Gardens. In 1932, Earnshaw sold his house and moved to Manor Farmhouse, West Dean, Sussex. His health began to decline, and his worked tailed off. In February 1935, having moved to Mill Road, Eastbourne, he was arrested for being drunk and incapable – he did not deny the charge, but in his defence his doctor told the magistrates (as recorded in The Eastbourne Gazette on 27 February 1935) that as a result of developing fits in around 1931, he was being treated by a drug which made him very easily affected by alcohol. While he admitted having drunk two double whiskeys after going for a walk on the sea front, he had no recollection of being drunk. The court was also told that his wife had been trying to stop him drinking by giving him very little money. He was fined ten shillings.

Earnshaw’s youngest child, Brian, had died in 1934, and in 1935 or 1936 the family moved back to London, to 11 Cambridge Place, Kensington, where Earnshaw died on 17 March 1937. He was buried in All Saints Churchyard, West Dean, alongside Brian – his gravestone records that he “died from war wounds”, an indication that despite his productivity he never fully recovered from his injuries. He left an estate valued at just £154. His widow subsequently moved to Cornwall, firstly, in 1944, to the small fishing village of Polruan, and the, two years later, to 3 St. Fimbarrus Road, Fowey, where she died on 5 November 1964, leaving an estate valued at £8,007.

PUBLICATIONS

Books illustrated by Harold C. Earnshaw

The Willoughby Captains by Talbot Baines Reed, Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton, 1907 (re-issue)

The Pretenders by Meredith Fletcher, Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton, 1907

Rivals and Chums by Kent Carr, W. & R. Chambers, 1908

The Rebel Cadets: A Tale of the ‘Britannia’ by Charles Gleig, W. & R. Chambers, 1908

The Attic Boarders by Raymond Jacberns, W. & R. Chambers, 1909

Aylwyn’s Friends by L.T. Meade, W. & R. Chambers, 1909

Two Schoolgirls of Florence by May Baldwin, W. & R. Chambers, 1910

The Chesterton Girl Graduates by L.T. Meade, W. & R. Chambers, 1910

For School and Country by Ralph Simmonds, Cassell & Co., 1911

Oscar: The Story of a Skye Terrier’s Adventures by L. Maclean Watt, W. & R. Chambers, 1911

St. Winifred’s, or The World of School by F.W. Farrar, Collins, 1911(?) (re-issue)

A Garland for Girls, Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton, 1911

The Girls’ Story Book, Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton, 1911

The Red Hussar by Regianld Horsley, W. & R. Chambers, 1912

The Puff-Puff Book, Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton, 1912

The Sign of Four by Arthur Conan Doyle, T. Nelson & Sons, 1912(?) (re-issue)

Gubbins Minor and Some Other Fellows: A Tale of School Life by Fred Whishaw, Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton, 1913 (re-issue)

The Book of Aeroplanes, Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton, 1913

The Chummy Book for All Boys and Girls who are Good Chums, T. Nelson & Sons, 1913

Girls of the Hamlet Club by Elsie J. Oxenham, W. & R. Chambers, 1914

The Potter’s Thumb by Flora Annie Steel, T. Nelson & Sons, 1914 (re-issue)

The Brown Book for Boys, Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton, 1914

The Green Book for Girls, Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton, 1914

Children’s Stories from Scott by Doris Ashley, Raphael Tuck & Sons, 1914

Princess Mary’s Gift Book, Hodder & Stoughton, 1914

At School with the Roundheads by Elsie J. Oxenham, W. & R. Chambers, 1915

Burr Junior: His Struggles and Studies at Old Browne’s School by George Manville Fenn, Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton, 1916 (re-issue)

Oliver Hastings, V.C.: A Realistic Story of the Great War by Escott Lynn, W. & C. Chambers, 1916

The Tuck-Shop Girl by Elsie J. Oxenham, W. & R. Chambers, 1916

Our Little One’s Second Book, Blackie & Son, 1916

The Girls’ Holiday Book, Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton, 1916

Billy the Scout, and His Day of Adventures by Ethel Talbot, T. Nelson & Sons, 1917

The Infants’ Magazine, S.W. Partridge, 1917

Knights of the Air by Escott Lynn, W. & R. Chambers, 1918

Line Up! A Tale of the New House at Farnstead by Harold Avery, Collins, 1918

Will of the Mill by George Manville Fenn, Collins, 1918 (re-issue)

The Cherry Chicks Book, Blackie & Son, 1918

The School of Ups and Downs by Elsie J. Oxenham, W. & R. Chambers, 1918

Rare Fun, Blackie & Son, 1918

Dick Whittington, and Red Riding Hood, Blackie & Son, 1918

The Rose Book for Girls, Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton, 1918(?)

Tommy of the Tanks by Escott Lynn, W. & R. Chambers, 1919

A Go-Ahead Schoolgirl by Elsie J. Oxenham, W. & R. Chambers, 1919

The Shaping of Jephson’s by Kent Carr, W. & R. Chambers, 1919

Puppy-Dog Tales, T. Nelson & Sons, 1919

My Story Book, Blackie & Son, 1919

Cats and Dogs for Little Folk, Blackie & Son, 1919

Pat’s Third Term by Christine Chaundler, O.U.P., 1920

The School Torment by Elsie J. Oxenham, W. & R. Chambers, 1920

The Scout’s Book by Bernard Everett (ed.), C. Arthur Pearson, 1920

Blackie’s Easy Story Book, Blackie & Son, 1920

The Happy Xmas Annual, Allied Newspapers, 1920

Home Sunshine, or Family Life by Catherine D. Bell, Collins, 1921 (re-issue)

The Big Row at Ranger’s: A Public School Story by Kent Carr, W. & R. Chambers, 1922

Happy Little Folk, Blackie & Son, 1922

Polly and Peter, Blackie & Son, 1922

The Jolly Party Book, Blackie & Son, 1922

Lots of Fun, Blackie & Son, 1923

The Washable Crayon Book of Trains, Valentine & Sons, 1923

The Fairystory Favourites Washable Crayon Book, Valentine & Sons, 1923

The Willoughby Captains by Talbot Baines Reed, Humphrey Milford/O.U.P., 1924 (re-issue)

The Looking Glass Annual, Middleton Publications, 1924

Martin’s Adventure by Cynthia Asquith, S.W. Partridge & Co., 1925

Stirring Stories for Boys, T. Nelson & Sons, 1925

The Flying Carpet by Cynthia Asquith (ed.), S.W. Partridge & Co., 1926

Smiles and Dimples by R.W. How and others, Blackie & Son, 1926

The Golden Budget of Nursery Stories by Frank Adams, Blackie & Son, 1929

The Victorian Schoolboys’ Story Book (various authors), Myer Emporium Ltd. (Australia), 1930

Come and Play, Blackie & Son, 1932

Country Sunshine, Blackie & Son, 1932

Seaside Fun, Blackie & Son, 1932

Our Great Day, Blackie & Son, 1932

All Smiles, Blackie & Son, 1932

Sunny Sands, Blackie & Son, 1932

Our Merry Games, Blackie & Son, 1932

Off on Holiday, Blackie & Son, 1932

Fine Times! Blackie & Son, 1932

Stories for Children from 8 to 10 Years Old by Amy Steedman, T. Nelson & Sons, 1933

Ivanhoe and Other Stories from Sir Walter Scott, Raphael Tuck & Sons, 1933

My Own Big Book, Blackie & Son, 1935

Happy Pictures, Blackie & Son, 1939

My Fine Big Book, Blackie & Son, 1939

As Nice as Nice Can Be, Blackie & Son, 1941

Dick Whittington and his Cat, Blackie & Son, 1941

Romps, Blackie & Son, 1948

Just What I Like! A Book of Stories, Pictures and Poems, Blackie & Son, 1951

Dates uncertain/not known/various

The Jolly Twins, Blackie & Son

At the Zoo, Blackie & Son

The Dingbats ABC: A Colouring Book, A.H. Allen & Co.

My Merry Pictures, Blackie & Son,

The Variety Painting Book, J. & L.R. Ltd., Merit Productions

The Puff Puff Book, Humphrey Milford/O.U.P.

The Favourite Story Book for Boys, T. Nelson & Sons,

The Lost Continent by Cutcliffe Hyne, Hutchinson & Co. (re-issue)

Jolly Book for Boys and Girls, T. Nelson & Sons

Blackie’s Little One’s Annual, Blackie & Son

Blackie’s Girls’ Annual, Blackie & Son

Blackie’s Children’s Annual, Blackie & Son

The Boys’ Treasury

The Jolly Book, T. Nelson & Sons

The Joy Book, Allied Newspapers

Once Upon a Time: Hulton’s Children’s Annual

McIlroy’s Schoolboys’ Annual, William McIlroy

2000AD 2054

2000AD 2054

2000AD 2053

2000AD 2053