Tuesday, May 31, 2016

Frank Bellamy and the Battle of Jutland

Today's celebrations of the Battle of Jutland bring back happy memories of working on Frank Bellamy's The Story of World War I, which was published by Book Palace Books a few years ago. The book is still available in hardback and softcover. It's a gorgeous book, one of my favourites amongst the many that I've worked on.

Monday, May 30, 2016

Perry's Picture Post part 10

"Photomechanical transfer" is a printing term describing a process for

producing photographic prints or offset printing plates from paper

negatives by a chemical transfer process rather than by exposure to

light. Amongst designers and editors, it is common practice to

call the glossy printers' proofs that are produced by this method PMTs.

For a long, long time, I had no knowledge or understanding of PMTs, or for that matter of Photostats (although, it's my believe that they are one and the same thing – “a rose by any other name” and all that jazz ). I certainly knew of them, as the weekly pasted-up dummies supplied by printer Eric Bemrose were littered with these strange images, giving both the printer and the editorial staff on Eagle a clear visual interpretation of what the finished pages would eventually look like. The PMTs pasted onto the dummy pages were produced by following the designers’ written instructions, so if anything had been incorrectly marked-up or wrongly sized, it would show up as an error on the dummy.

Anyway, as far as I was concerned, PMT machines had strictly been toys for the sole use of printers, so it it was quite a surprise to discover that not only did Hamlyn Books have two updated versions of the Grant Projector (as made by AGFA-Gevaert) that, housed within their specially darkened-out room towards the north-western corner of the big open-plan art-department, also had the facility of being able to produce PMTs.

In Part Nine, I described (in admittedly wearisome detail) how, by placing a piece of artwork onto the Grant’s moveable platform, I was able to obtain an image that was to the exact size I wanted to fit into a specific area. With this part of the process already done , it was time to create a PMT print.

With all overhead lighting having been turned off apart from a pair of dull-red bulbs, it was now safe to remove the A3 sheet of light-sensitive negative paper (or the smaller A4 sheet if the final picture was not all that large) from its doubly-wrapped packaging – black plastic bags inside sturdy cardboard containers.

I won’t say that the exposure was hit-or-miss but it took time before one got the hang of just how much exposure to give it. Three or four seconds was about right for quite small reductions whereas enlargements of 200% or 300% would be at least ten times that long. You need to understand that these PMTs were being used as a guide only and weren’t destined for one of the Royal Photographic Society's Fellowship Distinction Examinations, so a little too much or a little too little really didn’t matter all that much.

With the exposure over and done with, the paper negative was removed from the “Grant”, was married-up face-to-face with a paper positive of the same size and taken over to the processing machine.

The two sheets were encouraged to follow a pre-designated path through a series of rubberised rollers and plastic guides. Although the negative and positive sheets had been “married up” earlier, on feeding them into the processor, a chromium-plated bar about 1/8th of an inch thick immediately separated the two so that their journey through the processor could be made independently. Unlike photographic printing where the print is immersed in two entirely different chemicals – one being the developer while the other had ‘fixed’ the image (so that it would hopefully stay that way) – “PMTs” had just the one single, rectangular bath of liquid—filled to a level indicated by the manufacturers—to go through and that was the end of it. From beginning to end took little more than perhaps 45 seconds

The two sheets – the light sensitive negative and the chemically impregnated positive – ran independently along these plastic guides so that the two were kept well apart while the liquid chemical in the processing bath was given the opportunity to carry out its job, and they were only paired up and squeezed together again in the final moments by a pair of squeegee rollers as the processed sheets emerged towards the rear of the tank.

With the processed pair held between fingers and thumbs, it was advisable to give it a good 30 seconds before prising the two sheets apart – if you were too quick, the chemical reaction between negative and positive might not have been fully complete.

It was rather frustrating that these negatives could be used only the once and were then thrown away – for, should you need a second or more copies, you had to go through the whole procedure all over again.

The positive (which had been the “mechanical” side of the process) was not light sensitive and was simply stored in a clear plastic envelope on any shelf that was convenient. The positives weren't washed out in clean water afterwards either but just left to dry, ready for use when required.

I’ve not mentioned it before, but these Grant Projectors came with two lenses of differing focal lengths – there was the standard lens for producing prints that ranged anything from 30% up to 300% (as previously described in Part Nine), and then there was the second lens which allowed far greater reduction or enlargement—something in the region of between 12% and 1,500%. This second lens meant that 35mm colour transparencies could be enlarged up to 1,500% or perhaps even a smidgen higher.

When obtaining PMT prints from these colour slides, the Grant’s main lighting system needed to be changed, a complex procedure involving the pulling out of one plug and the shoving in of another! Due to the huge enlargements, the exposure needed for these often ran into several minutes – anything between five and fifteen. And this is where I come to the main point of telling you all this story.

I’d had a week off from work but had not gone away – I had stayed at home to carry out a few odd jobs (such as—and I’m not joking—building a swimming pool!). It was mid-week, probably Wednesday, and I planned to drive to Hamlyn House getting there at around 7:00 in the evening, by which time, I hoped, everyone would have gone home for the night.

Well, they almost all had, but when I entered the art room, I noted with some trepidation that, in the far corner (and directly opposite to where the repro cameras and PMT machines were housed), Brian Trodd and Glynn Pickerel were still hard at work toiling over their premium book projects. Undeterred, I tippy-toed the short distance over to where the darkroom was while hoping like mad that neither Brian nor Glynn had plans on using the darkroom facilities that night.

I remained inside that darkroom for a good three hours, for I’d had a large number of PMTs to produce – over a hundred. On finally emerging, I saw that both Brian and Glynn had already gone, and, with my bundle of illicit prints wrapped in an empty black plastic bag and tucked securely under my arm, I took the lift down to the ground level reception area. However, in attempting to open one of the two fully-glazed entrance-way doors, I was horrified to discover that they just wouldn’t budge – I was well-and-truly locked in.

Knowing that Hamlyn House also had an emergency exit stairwell, I’d gone back up to the eighth and tried again – but the emergency fire exit doors at the bottom were stuck fast and wouldn’t budge either.

From the eighth floor, I could see that lights were burning away on many of the upper floor levels of Astronaut House, the multi-office block on the other side of the railway track where a spill-over of staff from Hamlyn House were located. So I placed a call and spoke to the caretaker / receptionist outlining my current plight. With that, I returned to the ground level reception area and waited for his arrival. But when he came, he was not alone – for with him were six or seven boys in blue who had turned up in two Panda Cars with much flashing of lights.

Through the closed doors, I clearly heard one of them ask, “Do you recognise him?” to which the caretaker grudgingly replied, “Yes, I think I do. I think he works here in the art department.”

Five minutes later, I was back in my own car driving back to Farnham and occasionally going through a giggling spasm. However, the really amusing tailpiece of that little caper was that for several days following, there were in-depth enquiries as to who this unknown person that had infiltrated Hamlyn Books was. They never did find out, for I was officially on holiday for a few more days and therefore wasn't around to be asked.

During my time at Hamlyn’s, I did get involved in a handful of extra-curricular photographic jaunts. The pictures and article shown above had been typical of a “chicken and egg” conundrum – I cannot recall now if I had just taken a load of pictures of my son and daughter with some of their school chums . . . following on from which the article had been put together, or whether the text had been written first and I’d then gone out and captured the shots. Sometimes it happened that way – anyway, it was a good excuse to grab a few snaps of the kids while enjoying ourselves by munching through a pile of fish-paste sarnies!

The editorial section on the 5th floor had consisted (amongst others) of Chris Spencer, Tessa Bridger (who I suppose was the senior Sub-Editor), Peter Robins and Graeme Cook . . . although this latter pair had officially worked full-time on Hamlyn All-Colour Paperbacks. There was actually a fifth whose name was Susannah Holden and it was with her that I’d passed a couple of interesting afternoons up in London.

Following our two ventures out, Susannah had written an article about Vidal Sassoon’s Hairdressing Salon in Baker Street for the Daily Mirror Book for Girls called “Crowning Glories” . . . although it was a bit of a shame that the “Father of Modern Hairdressing” himself hadn’t been present which would have made the exercise just a tad more riveting. The other piece she wrote was called “The Twenty Pound Walk”, where, I note with interest, she used the pen-name Sue Kirkpatrick for reasons best known to herself.

Out of the blue, Chris Spencer approached me one day to say that Graeme Cook had been sent an invitation to fly from nearby RAF Northolt and go down to RNAS Yeovilton in Somerset. For some reason Graeme couldn’t go and had wondered if Chris would care to take his place. The assignment was to write an article about the Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber which had had a key role in the sinking of the pride of Germany’s fleet – the Bismark. It would appear that one had just been lovingly restored back to its former glory. Chris would write the story and he hoped that I would go along with him so that I could take a series of pictures.

On another day, Graeme Cook suggested that he and I should drive up to Catterick in Yorkshire where the White Helmets motorcycle display team had their base and where they carried out their intensive training. The original plan had been that we would travel up in Graeme’s car, but at the last minute, he rang through to say that as his car had been rendered unserviceable, would it be OK if we used mine instead.

On the drive up and seeing the sights as offered by the Great North Road (the A1), Graeme related how, two days earlier, he and his wife had had yet another domestic argument. It would seem that his wife had gone upstairs in a fuming rage, locked the bedroom door and, on spotting a concrete hollow block (although Graeme didn’t actually explain why a concrete hollow block would have been lying around in their bedroom), she had opened the window and thrown the block fair and square down onto the front windscreen of his car. Thus rendering it unusable until he found the time to get it fixed.

At Catterick, we were introduced to Sergeant George Garside and, although Graeme seemed to have been readily accepted as being “one of the boys”, I got the clear vibes that Garside considered me to be little more than a toffee-nosed snob. Anyway, after being given some lunch in the Sergeants’ Mess, we were each kitted out with waterproofed denims and a pair of heavy boots. Graeme had already warned me that the conditions at Catterick were likely to be muddy and I’d taken my Wellington Boots with me—which I'd left outside Garside’s office.

Much of the fun we’d had was with Graeme haring here, there and everywhere on the slopes of an exceedingly muddy assault course while I did my best to (a) stand upright and (b) capture the action being presented to me. With that part of the procedure over, it was now time to meet with Garside’s White Helmets display team who, thankfully, were in the middle of practicing their “four-leaf clover” routine on firm ground that was nice and dry by comparison and covered in oodles of nicely-mown grass.

This part of their act proceeded thus: In the form of a cross and perhaps twenty-feet apart, four 8-inch high wooden ramps were positioned so that the rider – having ridden over one – was momentarily propelled about three feet into the air along with his machine and would remain airborne for a second or so. The trick was that two riders coming from opposing directions (say north and south) would pass each other whilst aloft – this was followed a second or so later by another pair of riders doing much the same thing but from an east/west direction. With a team consisting of eight, ten or twelve riders, they went round and round, leaping over the ramps thus forming a “four-leaf clover” pattern.

Photographically – and as seen from ground level – the chorographical magic of the manoeuvre was lost, for, ideally, it would have been best seen from either a helicopter or the second floor balcony of a block of flats. But as neither a helicopter nor a block of flats was at my disposal, I opted for the next-best thing – which was to ride pillion on one of the participating machines.

Garside readily agreed, but as I was about to sit astride the machine that he’d chosen for me, he said fairly forcefully: “No, not that way – you have to travel backwards!”

“Backwards?” I gulped (I could almost feel the smirk he had been doing his best to conceal).

Still backwards I went, and it was probably the most frightening thing I’d ever attempted – the reason being that with the camera held in one hand and nothing to grab onto with the other, each time the rider surged forward for his forthcoming flight over the central point, it was only by clenching my knees tightly around the bike’s framework that I prevented myself from taking a tumble. I managed to fire off a few shots, but all in all, they were pretty unusable.

At the end of the ride, Garside asked pleasantly:

“Did you get what you wanted?” probably knowing fully well that I hadn’t. So I said to him:

“I’d like to go round again, but this time, I shall face forwards and shoot over the driver’s shoulder.” The smile upon his lips died as he was forced to concede that perhaps the “toffee-nosed-snob” hadn’t been such a wimp after all.

But Garside had the last laugh. Approaching London after our long return journey down the A1, it suddenly occurred to me that my Wellington Boots were still sitting outside Garside’s office. Hey Ho.

Roger Perry

The Philippines

Coming Soon: In Part Eleven, big changes are in the air as I take my leave from the book empire of Paul Hamlyn and return back into the world of comics.

(* Many thanks to Phil Rushton for scans of the Fairey Swordfish feature.)

For a long, long time, I had no knowledge or understanding of PMTs, or for that matter of Photostats (although, it's my believe that they are one and the same thing – “a rose by any other name” and all that jazz ). I certainly knew of them, as the weekly pasted-up dummies supplied by printer Eric Bemrose were littered with these strange images, giving both the printer and the editorial staff on Eagle a clear visual interpretation of what the finished pages would eventually look like. The PMTs pasted onto the dummy pages were produced by following the designers’ written instructions, so if anything had been incorrectly marked-up or wrongly sized, it would show up as an error on the dummy.

Anyway, as far as I was concerned, PMT machines had strictly been toys for the sole use of printers, so it it was quite a surprise to discover that not only did Hamlyn Books have two updated versions of the Grant Projector (as made by AGFA-Gevaert) that, housed within their specially darkened-out room towards the north-western corner of the big open-plan art-department, also had the facility of being able to produce PMTs.

In Part Nine, I described (in admittedly wearisome detail) how, by placing a piece of artwork onto the Grant’s moveable platform, I was able to obtain an image that was to the exact size I wanted to fit into a specific area. With this part of the process already done , it was time to create a PMT print.

With all overhead lighting having been turned off apart from a pair of dull-red bulbs, it was now safe to remove the A3 sheet of light-sensitive negative paper (or the smaller A4 sheet if the final picture was not all that large) from its doubly-wrapped packaging – black plastic bags inside sturdy cardboard containers.

I won’t say that the exposure was hit-or-miss but it took time before one got the hang of just how much exposure to give it. Three or four seconds was about right for quite small reductions whereas enlargements of 200% or 300% would be at least ten times that long. You need to understand that these PMTs were being used as a guide only and weren’t destined for one of the Royal Photographic Society's Fellowship Distinction Examinations, so a little too much or a little too little really didn’t matter all that much.

With the exposure over and done with, the paper negative was removed from the “Grant”, was married-up face-to-face with a paper positive of the same size and taken over to the processing machine.

The two sheets were encouraged to follow a pre-designated path through a series of rubberised rollers and plastic guides. Although the negative and positive sheets had been “married up” earlier, on feeding them into the processor, a chromium-plated bar about 1/8th of an inch thick immediately separated the two so that their journey through the processor could be made independently. Unlike photographic printing where the print is immersed in two entirely different chemicals – one being the developer while the other had ‘fixed’ the image (so that it would hopefully stay that way) – “PMTs” had just the one single, rectangular bath of liquid—filled to a level indicated by the manufacturers—to go through and that was the end of it. From beginning to end took little more than perhaps 45 seconds

The two sheets – the light sensitive negative and the chemically impregnated positive – ran independently along these plastic guides so that the two were kept well apart while the liquid chemical in the processing bath was given the opportunity to carry out its job, and they were only paired up and squeezed together again in the final moments by a pair of squeegee rollers as the processed sheets emerged towards the rear of the tank.

With the processed pair held between fingers and thumbs, it was advisable to give it a good 30 seconds before prising the two sheets apart – if you were too quick, the chemical reaction between negative and positive might not have been fully complete.

It was rather frustrating that these negatives could be used only the once and were then thrown away – for, should you need a second or more copies, you had to go through the whole procedure all over again.

The positive (which had been the “mechanical” side of the process) was not light sensitive and was simply stored in a clear plastic envelope on any shelf that was convenient. The positives weren't washed out in clean water afterwards either but just left to dry, ready for use when required.

I’ve not mentioned it before, but these Grant Projectors came with two lenses of differing focal lengths – there was the standard lens for producing prints that ranged anything from 30% up to 300% (as previously described in Part Nine), and then there was the second lens which allowed far greater reduction or enlargement—something in the region of between 12% and 1,500%. This second lens meant that 35mm colour transparencies could be enlarged up to 1,500% or perhaps even a smidgen higher.

When obtaining PMT prints from these colour slides, the Grant’s main lighting system needed to be changed, a complex procedure involving the pulling out of one plug and the shoving in of another! Due to the huge enlargements, the exposure needed for these often ran into several minutes – anything between five and fifteen. And this is where I come to the main point of telling you all this story.

I’d had a week off from work but had not gone away – I had stayed at home to carry out a few odd jobs (such as—and I’m not joking—building a swimming pool!). It was mid-week, probably Wednesday, and I planned to drive to Hamlyn House getting there at around 7:00 in the evening, by which time, I hoped, everyone would have gone home for the night.

Well, they almost all had, but when I entered the art room, I noted with some trepidation that, in the far corner (and directly opposite to where the repro cameras and PMT machines were housed), Brian Trodd and Glynn Pickerel were still hard at work toiling over their premium book projects. Undeterred, I tippy-toed the short distance over to where the darkroom was while hoping like mad that neither Brian nor Glynn had plans on using the darkroom facilities that night.

I remained inside that darkroom for a good three hours, for I’d had a large number of PMTs to produce – over a hundred. On finally emerging, I saw that both Brian and Glynn had already gone, and, with my bundle of illicit prints wrapped in an empty black plastic bag and tucked securely under my arm, I took the lift down to the ground level reception area. However, in attempting to open one of the two fully-glazed entrance-way doors, I was horrified to discover that they just wouldn’t budge – I was well-and-truly locked in.

Knowing that Hamlyn House also had an emergency exit stairwell, I’d gone back up to the eighth and tried again – but the emergency fire exit doors at the bottom were stuck fast and wouldn’t budge either.

From the eighth floor, I could see that lights were burning away on many of the upper floor levels of Astronaut House, the multi-office block on the other side of the railway track where a spill-over of staff from Hamlyn House were located. So I placed a call and spoke to the caretaker / receptionist outlining my current plight. With that, I returned to the ground level reception area and waited for his arrival. But when he came, he was not alone – for with him were six or seven boys in blue who had turned up in two Panda Cars with much flashing of lights.

Through the closed doors, I clearly heard one of them ask, “Do you recognise him?” to which the caretaker grudgingly replied, “Yes, I think I do. I think he works here in the art department.”

Five minutes later, I was back in my own car driving back to Farnham and occasionally going through a giggling spasm. However, the really amusing tailpiece of that little caper was that for several days following, there were in-depth enquiries as to who this unknown person that had infiltrated Hamlyn Books was. They never did find out, for I was officially on holiday for a few more days and therefore wasn't around to be asked.

During my time at Hamlyn’s, I did get involved in a handful of extra-curricular photographic jaunts. The pictures and article shown above had been typical of a “chicken and egg” conundrum – I cannot recall now if I had just taken a load of pictures of my son and daughter with some of their school chums . . . following on from which the article had been put together, or whether the text had been written first and I’d then gone out and captured the shots. Sometimes it happened that way – anyway, it was a good excuse to grab a few snaps of the kids while enjoying ourselves by munching through a pile of fish-paste sarnies!

The editorial section on the 5th floor had consisted (amongst others) of Chris Spencer, Tessa Bridger (who I suppose was the senior Sub-Editor), Peter Robins and Graeme Cook . . . although this latter pair had officially worked full-time on Hamlyn All-Colour Paperbacks. There was actually a fifth whose name was Susannah Holden and it was with her that I’d passed a couple of interesting afternoons up in London.

Following our two ventures out, Susannah had written an article about Vidal Sassoon’s Hairdressing Salon in Baker Street for the Daily Mirror Book for Girls called “Crowning Glories” . . . although it was a bit of a shame that the “Father of Modern Hairdressing” himself hadn’t been present which would have made the exercise just a tad more riveting. The other piece she wrote was called “The Twenty Pound Walk”, where, I note with interest, she used the pen-name Sue Kirkpatrick for reasons best known to herself.

Out of the blue, Chris Spencer approached me one day to say that Graeme Cook had been sent an invitation to fly from nearby RAF Northolt and go down to RNAS Yeovilton in Somerset. For some reason Graeme couldn’t go and had wondered if Chris would care to take his place. The assignment was to write an article about the Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber which had had a key role in the sinking of the pride of Germany’s fleet – the Bismark. It would appear that one had just been lovingly restored back to its former glory. Chris would write the story and he hoped that I would go along with him so that I could take a series of pictures.

On another day, Graeme Cook suggested that he and I should drive up to Catterick in Yorkshire where the White Helmets motorcycle display team had their base and where they carried out their intensive training. The original plan had been that we would travel up in Graeme’s car, but at the last minute, he rang through to say that as his car had been rendered unserviceable, would it be OK if we used mine instead.

On the drive up and seeing the sights as offered by the Great North Road (the A1), Graeme related how, two days earlier, he and his wife had had yet another domestic argument. It would seem that his wife had gone upstairs in a fuming rage, locked the bedroom door and, on spotting a concrete hollow block (although Graeme didn’t actually explain why a concrete hollow block would have been lying around in their bedroom), she had opened the window and thrown the block fair and square down onto the front windscreen of his car. Thus rendering it unusable until he found the time to get it fixed.

At Catterick, we were introduced to Sergeant George Garside and, although Graeme seemed to have been readily accepted as being “one of the boys”, I got the clear vibes that Garside considered me to be little more than a toffee-nosed snob. Anyway, after being given some lunch in the Sergeants’ Mess, we were each kitted out with waterproofed denims and a pair of heavy boots. Graeme had already warned me that the conditions at Catterick were likely to be muddy and I’d taken my Wellington Boots with me—which I'd left outside Garside’s office.

Much of the fun we’d had was with Graeme haring here, there and everywhere on the slopes of an exceedingly muddy assault course while I did my best to (a) stand upright and (b) capture the action being presented to me. With that part of the procedure over, it was now time to meet with Garside’s White Helmets display team who, thankfully, were in the middle of practicing their “four-leaf clover” routine on firm ground that was nice and dry by comparison and covered in oodles of nicely-mown grass.

This part of their act proceeded thus: In the form of a cross and perhaps twenty-feet apart, four 8-inch high wooden ramps were positioned so that the rider – having ridden over one – was momentarily propelled about three feet into the air along with his machine and would remain airborne for a second or so. The trick was that two riders coming from opposing directions (say north and south) would pass each other whilst aloft – this was followed a second or so later by another pair of riders doing much the same thing but from an east/west direction. With a team consisting of eight, ten or twelve riders, they went round and round, leaping over the ramps thus forming a “four-leaf clover” pattern.

Photographically – and as seen from ground level – the chorographical magic of the manoeuvre was lost, for, ideally, it would have been best seen from either a helicopter or the second floor balcony of a block of flats. But as neither a helicopter nor a block of flats was at my disposal, I opted for the next-best thing – which was to ride pillion on one of the participating machines.

Garside readily agreed, but as I was about to sit astride the machine that he’d chosen for me, he said fairly forcefully: “No, not that way – you have to travel backwards!”

“Backwards?” I gulped (I could almost feel the smirk he had been doing his best to conceal).

Still backwards I went, and it was probably the most frightening thing I’d ever attempted – the reason being that with the camera held in one hand and nothing to grab onto with the other, each time the rider surged forward for his forthcoming flight over the central point, it was only by clenching my knees tightly around the bike’s framework that I prevented myself from taking a tumble. I managed to fire off a few shots, but all in all, they were pretty unusable.

At the end of the ride, Garside asked pleasantly:

“Did you get what you wanted?” probably knowing fully well that I hadn’t. So I said to him:

“I’d like to go round again, but this time, I shall face forwards and shoot over the driver’s shoulder.” The smile upon his lips died as he was forced to concede that perhaps the “toffee-nosed-snob” hadn’t been such a wimp after all.

But Garside had the last laugh. Approaching London after our long return journey down the A1, it suddenly occurred to me that my Wellington Boots were still sitting outside Garside’s office. Hey Ho.

Roger Perry

The Philippines

Coming Soon: In Part Eleven, big changes are in the air as I take my leave from the book empire of Paul Hamlyn and return back into the world of comics.

(* Many thanks to Phil Rushton for scans of the Fairey Swordfish feature.)

Saturday, May 28, 2016

Perry's Picture Post part 9

About two weeks after the stunning news that Neil Armstrong had left a boot-print upon the Moon’s surface, Brian Cullen – my immediate boss – limped over to my workspace area bringing with him an animated man who turned out to be Oliver Postgate.

For those of you who might be old enough to remember the occasion, although the Lunar Module touched down at 20:18 UTC on July 20th, 1969, it was over six-and-a-half hours later before Armstrong finally opened up the LM’s hatch and made his “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind" speech. In the hours while we waited with baited breath for this magnificent event to happen (for television pictures of the occasion were being broadcast the world over), Oliver Postgate hadn’t been idle . . . he’d dreamed up the idea of The Clangers – pink-knitted aliens who spoke a language that sounded like a sliding whistle.

As Hamlyn Books were already producing Postgate’s The Pogles Annual, he’d hot-footed up from Broadstairs (East Kent) to put in a personal appearance in the hope that Hamlyn’s might now take this new creation of his on as well. With John Kingsford and I already struggling to put 24 Christmas annuals together in a year, what could the addition of one more do to hurt?

Although it was great to have John as my No.2, with the editorial department only three floors down from the eighth, I spent virtually every lunch break in the company of Chris Spencer and his work companion, Peter Robins. This was not in any way a slight to John, who lived only a few miles away in Twickenham, and drove home so that he could take his midday meal alongside his loving wife, Fay.

The pattern was invariably the same. Along with Chris (one of the two sub-editors in the Annuals Section, the other being Tessa Bridger), we would buy a total of 9 rolls and 6oz of spam from the delicatessen store just yards away from the front door of Hamlyn House. From there, we would either drive over to the River Thames, where we would assemble and consume our midday sustenance before calling into the local pub for a quick game of darts; or we would go slightly further afield to Richmond Park, where we would fill our stomachs while enjoying the company of our four-footed chums who would nonchalantly munch at the grass nearby.

Every now and then, Bob Prior would get in touch to ask if I could do this or that for him, which mostly I managed to do on a Saturday or Sunday. He had become involved with a pair of shady (sleazy?) individuals called the Gold brothers who published (amongst other things) top-shelf soft porn. These highly-educational booklets were A5 in size, with a full colour cover and 32 black and white pages that related in photo form such adventures as that of the milkman who happened to be on hand to help a struggling housewife with her groceries, and the reward he received.

They took about an hour – maybe two – to shoot; Bob paid me £10 for my time. It was he who did all the running around, finding the models and locations; he also organised the developing and printing of the exposed films. As there was no design required, he just handed over a set of 32 black and white prints together with the colour transparency for the cover. So were the brothers sleazy? To make their issued cheques legally binding, both brothers had to sign on the dotted line, so, if it came to their notice that a visitor in need of payment was approaching their office, one or other would step out the back door and hide somewhere until the contributor got tired of waiting.

Along with John Kingsford, I kept my head down and got on with my work. Perhaps we cut ourselves off more than I realised, for, after several months, I discovered that Brian Cullen and John Youe had been telling each other that they had no idea what we were up to, although there had been no complaints or criticisms over my designs when they were seen in print.

Not everything went as smoothly as it should, however. One rather expensive error had come about while producing the Daily Mirror Book of Football.

In Part One of this series, I spoke extensively of Theodore “Wil” Wilson, the representative from Syndication International who called in on a regular basis so that Shirley Dean might choose pictures for use in Girl. By this time, Wil had moved on and was now working from home, having started up a syndicating business of his own. In his place came Ron Ahrens, a smaller, wiry man of around 30, whose passion was to spend his Saturday afternoons squatting on the touchline of some football ground, snapping away with one or other of the cameras strung around his neck.

I believe this was when I first met Ron. He would visit me at Hamlyn House with the text already written and a pile of photographs all neatly filed and identified so that John Kingsford and I had few problems matching up the pictures to the text when it came to designing the pages. When you realise how little interest John or I had in seeing twenty-two strapping fellahs kicking a ball around, the idea of the two of us putting together a book on the subject seems even more ludicrous.

Some while later when all the copy had been typeset, the layouts completed and captions written, the book was ready to be sent off to press. We had one final job still to do. Each picture had to be identified with the name of the intended book; it had to have the page number written upon it showing where in the book it was intended to go—if there should be more than one picture on that page, they were given an “A”, “B” or “C” etc. on the back; and, finally, a rectangular box drawn in pencil on the photograph’s back telling the repro house the area that the designer wants to use together with the size that it is to be reduced or enlarged to.

These instructions on the rear of each picture had to be written on a hard surface or the impression made by the pencil could easily damage the photographic image. With 200 or more photographs going into the book, having to write the name “Daily Mirror Book of Football” on every single one . . . well, let's just say that there are other things more exciting to do in life.

Either John or I had the bright idea of rubber-stamping the title using a John Bull printing outfit that we’d found from somewhere – perhaps it had been sitting on some other designer’s desk. And, having rubber-stamped all the pictures, the book was sent to press. But . . . disaster!

John and I had failed to make quite sure that the ink was quite dry before placing each photo onto the growing pile. We learnt later that the repro house had had to spend hours retouching all the pictures where the image was spoiled by John Bull printing set ink. Hopefully the bodger given that task was fanatical about football!

With Bob Prior knowing that I had quite a library of animal pictures at my disposal, collected for the most part during my days at Century 21, he had secured a commission to supply somebody-or-other—I’m not sure if I ever knew who the publisher was—with enough material to print four animal books along the lines of those I’d produced while still working in May’s Court.

In the process of producing a book of this type, one cannot just size a picture willy-nilly and pass the instructions onto the repro house. In order to keep prices at a reasonable level, one needs to keep the number of varying proportions to an absolute minimum – in a book of 32 pages for example, there might be just three or four different proportional variations from the set of original 35mm transparencies. More proportions would result in the price of the book being increased—and there was quite a hefty charge from the repro house each time the operator had to alter the settings.

One invaluable piece of equipment was the Grant Projector, lovingly called “The Grant”. It was a mechanical contraption used to magnify or reduce artwork and project the image onto a sheet of semi-translucent paper so that it could be traced off. The “Grant” was about 20” wide by 20” deep and something in the region of 42” from its four brass, bed-like casters to the quarter-inch-plate viewing glass.

Apart from the main on/off switch that controlled the interior lighting system, there were just two controls: one that raised or lowered the interior platform onto which the item being viewed was placed; and the other that raised or lowered the lens assembly that brought the viewed object into sharp focus.

Later models had more powerful halogen lamps, but, in the 1960s, light came from eight 150-watt tungsten bulbs arranged in a circle, which offered fairly even lighting all round the item being viewed. These were placed in what looked like an inverted aluminium washing-up bowl with a large hole at its centre. It was at this centre that the lens was secured on a sort of three pin bayonet arrangement. By raising or lowering the platform, while at the same time raising or lowering the lens together with its assembly of eight bulbs, the object’s image was projected onto the quarter-inch-plate viewing glass anything between one third and three times its original size (33% to 300%).

To assist the operator, not only did “Mr Grant” supply a nine-inch high foot stool, so that the designer could work in relative comfort while peering down upon the viewing glass, but he also installed a fold-away pram-hood type affair to reduce extraneous light to a minimum. Using thin-but-good-quality layout paper, the designer could then trace off the projected image to the exact size he or she wanted.

There is many a designer who has shed a tear at the memory of these God-given contraptions.

THE SEVENTIES ILLUSTRATOR'S PRAYER by Raymond Briggs *

The Philippines

Coming soon: In Part Ten . . . now that I have introduced the Grant Projector, I need to discuss PMTs and reveal what happened when, sneaking into Hamlyn House after everyone else had gone home, I discovered that however hard I tried I just could not get out of the building again!

(* © Raymond Briggs; originally published in the Association of Illustrators magazine Illustrators in the late 1970s and reproduced from Mike Dempsey's Graphic Journey blog., as are the image of the grant projector and the cartoon by Arthur Robbins.)

For those of you who might be old enough to remember the occasion, although the Lunar Module touched down at 20:18 UTC on July 20th, 1969, it was over six-and-a-half hours later before Armstrong finally opened up the LM’s hatch and made his “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind" speech. In the hours while we waited with baited breath for this magnificent event to happen (for television pictures of the occasion were being broadcast the world over), Oliver Postgate hadn’t been idle . . . he’d dreamed up the idea of The Clangers – pink-knitted aliens who spoke a language that sounded like a sliding whistle.

As Hamlyn Books were already producing Postgate’s The Pogles Annual, he’d hot-footed up from Broadstairs (East Kent) to put in a personal appearance in the hope that Hamlyn’s might now take this new creation of his on as well. With John Kingsford and I already struggling to put 24 Christmas annuals together in a year, what could the addition of one more do to hurt?

Although it was great to have John as my No.2, with the editorial department only three floors down from the eighth, I spent virtually every lunch break in the company of Chris Spencer and his work companion, Peter Robins. This was not in any way a slight to John, who lived only a few miles away in Twickenham, and drove home so that he could take his midday meal alongside his loving wife, Fay.

The pattern was invariably the same. Along with Chris (one of the two sub-editors in the Annuals Section, the other being Tessa Bridger), we would buy a total of 9 rolls and 6oz of spam from the delicatessen store just yards away from the front door of Hamlyn House. From there, we would either drive over to the River Thames, where we would assemble and consume our midday sustenance before calling into the local pub for a quick game of darts; or we would go slightly further afield to Richmond Park, where we would fill our stomachs while enjoying the company of our four-footed chums who would nonchalantly munch at the grass nearby.

Every now and then, Bob Prior would get in touch to ask if I could do this or that for him, which mostly I managed to do on a Saturday or Sunday. He had become involved with a pair of shady (sleazy?) individuals called the Gold brothers who published (amongst other things) top-shelf soft porn. These highly-educational booklets were A5 in size, with a full colour cover and 32 black and white pages that related in photo form such adventures as that of the milkman who happened to be on hand to help a struggling housewife with her groceries, and the reward he received.

They took about an hour – maybe two – to shoot; Bob paid me £10 for my time. It was he who did all the running around, finding the models and locations; he also organised the developing and printing of the exposed films. As there was no design required, he just handed over a set of 32 black and white prints together with the colour transparency for the cover. So were the brothers sleazy? To make their issued cheques legally binding, both brothers had to sign on the dotted line, so, if it came to their notice that a visitor in need of payment was approaching their office, one or other would step out the back door and hide somewhere until the contributor got tired of waiting.

Along with John Kingsford, I kept my head down and got on with my work. Perhaps we cut ourselves off more than I realised, for, after several months, I discovered that Brian Cullen and John Youe had been telling each other that they had no idea what we were up to, although there had been no complaints or criticisms over my designs when they were seen in print.

Not everything went as smoothly as it should, however. One rather expensive error had come about while producing the Daily Mirror Book of Football.

In Part One of this series, I spoke extensively of Theodore “Wil” Wilson, the representative from Syndication International who called in on a regular basis so that Shirley Dean might choose pictures for use in Girl. By this time, Wil had moved on and was now working from home, having started up a syndicating business of his own. In his place came Ron Ahrens, a smaller, wiry man of around 30, whose passion was to spend his Saturday afternoons squatting on the touchline of some football ground, snapping away with one or other of the cameras strung around his neck.

I believe this was when I first met Ron. He would visit me at Hamlyn House with the text already written and a pile of photographs all neatly filed and identified so that John Kingsford and I had few problems matching up the pictures to the text when it came to designing the pages. When you realise how little interest John or I had in seeing twenty-two strapping fellahs kicking a ball around, the idea of the two of us putting together a book on the subject seems even more ludicrous.

Some while later when all the copy had been typeset, the layouts completed and captions written, the book was ready to be sent off to press. We had one final job still to do. Each picture had to be identified with the name of the intended book; it had to have the page number written upon it showing where in the book it was intended to go—if there should be more than one picture on that page, they were given an “A”, “B” or “C” etc. on the back; and, finally, a rectangular box drawn in pencil on the photograph’s back telling the repro house the area that the designer wants to use together with the size that it is to be reduced or enlarged to.

These instructions on the rear of each picture had to be written on a hard surface or the impression made by the pencil could easily damage the photographic image. With 200 or more photographs going into the book, having to write the name “Daily Mirror Book of Football” on every single one . . . well, let's just say that there are other things more exciting to do in life.

Either John or I had the bright idea of rubber-stamping the title using a John Bull printing outfit that we’d found from somewhere – perhaps it had been sitting on some other designer’s desk. And, having rubber-stamped all the pictures, the book was sent to press. But . . . disaster!

John and I had failed to make quite sure that the ink was quite dry before placing each photo onto the growing pile. We learnt later that the repro house had had to spend hours retouching all the pictures where the image was spoiled by John Bull printing set ink. Hopefully the bodger given that task was fanatical about football!

With Bob Prior knowing that I had quite a library of animal pictures at my disposal, collected for the most part during my days at Century 21, he had secured a commission to supply somebody-or-other—I’m not sure if I ever knew who the publisher was—with enough material to print four animal books along the lines of those I’d produced while still working in May’s Court.

In the process of producing a book of this type, one cannot just size a picture willy-nilly and pass the instructions onto the repro house. In order to keep prices at a reasonable level, one needs to keep the number of varying proportions to an absolute minimum – in a book of 32 pages for example, there might be just three or four different proportional variations from the set of original 35mm transparencies. More proportions would result in the price of the book being increased—and there was quite a hefty charge from the repro house each time the operator had to alter the settings.

One invaluable piece of equipment was the Grant Projector, lovingly called “The Grant”. It was a mechanical contraption used to magnify or reduce artwork and project the image onto a sheet of semi-translucent paper so that it could be traced off. The “Grant” was about 20” wide by 20” deep and something in the region of 42” from its four brass, bed-like casters to the quarter-inch-plate viewing glass.

Apart from the main on/off switch that controlled the interior lighting system, there were just two controls: one that raised or lowered the interior platform onto which the item being viewed was placed; and the other that raised or lowered the lens assembly that brought the viewed object into sharp focus.

Later models had more powerful halogen lamps, but, in the 1960s, light came from eight 150-watt tungsten bulbs arranged in a circle, which offered fairly even lighting all round the item being viewed. These were placed in what looked like an inverted aluminium washing-up bowl with a large hole at its centre. It was at this centre that the lens was secured on a sort of three pin bayonet arrangement. By raising or lowering the platform, while at the same time raising or lowering the lens together with its assembly of eight bulbs, the object’s image was projected onto the quarter-inch-plate viewing glass anything between one third and three times its original size (33% to 300%).

To assist the operator, not only did “Mr Grant” supply a nine-inch high foot stool, so that the designer could work in relative comfort while peering down upon the viewing glass, but he also installed a fold-away pram-hood type affair to reduce extraneous light to a minimum. Using thin-but-good-quality layout paper, the designer could then trace off the projected image to the exact size he or she wanted.

There is many a designer who has shed a tear at the memory of these God-given contraptions.

THE SEVENTIES ILLUSTRATOR'S PRAYER by Raymond Briggs *

Our Enlarger,Roger Perry

Which art in College,

The Grant be Thy Name.

Thy Copy come.

Thy light be on,

In Art as It is in Design.

Give us this Way our Easy Bread,

And Forgive us our Tracepapers,

As we Forgive Them that Trace Off before us.

And Lead us not into Life Classes;

But Deliver us from Drawing:

For Thine is The Kodak,

The Polaroid and Pentax,

For Agfa and Agfa.

Ah Me!

The Philippines

Coming soon: In Part Ten . . . now that I have introduced the Grant Projector, I need to discuss PMTs and reveal what happened when, sneaking into Hamlyn House after everyone else had gone home, I discovered that however hard I tried I just could not get out of the building again!

(* © Raymond Briggs; originally published in the Association of Illustrators magazine Illustrators in the late 1970s and reproduced from Mike Dempsey's Graphic Journey blog., as are the image of the grant projector and the cartoon by Arthur Robbins.)

Friday, May 27, 2016

Comic Cuts - 27 May 2016

Working for home on my own means that I'm a huge consumer of audio. Some people like absolute silence when they're working, and I usually start the day that way. I'm usually in front of the computer by 7.30 am at the latest, occasionally as early as 6.30. I have a morning walk that starts around 8.00 and I'm back in front of the computer from 8.30 until 11.00am, when I take a break.

As I usually tackle a lot of mail in the morning, I tend to keep things fairly quiet so I can concentrate; the bits of your brain that interpret lyrics are also the bits of your brain that you need for writing, so anything spoken word or with lyrics can distract or, as I've found in the past, go through one ear and out the other without making any impact. I once listened to a whole 90 minute Agatha Christie mystery drama and at the end of it I had no idea who had been murdered, let alone who the murderer was.

In the afternoon I'm often revamping press releases, sorting out artwork and putting together material for the Hotel Business website, which requires less intense concentration, so I'll play music or listen to podcasts. I've mentioned the latter relatively recently, so I'll limit myself to mentioning that the second part of the latest epic from The Secret History of Hollywood was released recently—part two of the history of Warner Bros and the gangster cycle of movies starring the likes of James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson. The two episodes so far amount to about 10 1/2 hours of listening, and if you have any interest in old Hollywood, they're well worth it. Check out some of the other episodes about the Universal horror movies, Basil Rathbone's Sherlock Holmes and the life of Alfred Hitchcock... they're all worth listening to.

Easier on the ears, even when I'm trying to concentrate, is music. I've always been a fan of rock at the harder end of the spectrum, but I've mellowed—or "mellotron'd"—over the years and my tastes for extended listening these days are towards the progressive end of rock. (That "mellotron'd" gag is for other prog fans!)

Two of my favourite bands have albums out today. I mentioned a couple of week's ago that I was ridiculously excited that Frost* have a new record coming out. At the time of writing, I'm still waiting for my pre-ordered copy to arrive.

What I forgot to mention was that Big Big Train also have a new album out. Their last, English Electric, was my favourite album from a couple of years ago. For Folklore they've expanded their cast of musicians to include a violin player and additional keyboards. The results are a delight. There's a very good review here, which notes some weaknesses in the album (it's not quite up to the sublime brilliance of The Underfall Yard or English Electric) and, as reviewer Brad Birzer puts it, "Folklore is not the easiest of BBT's releases to grasp, nor is it their best. Regardless, it is incredibly good."

This leaves me in something of a dilemma... to recommend you all rush out and buy Folklore or to say rush out and buy The Underfall Yard and English Electric and then come back to Folklore. I think the latter. It's a progression of the band's sound and you need to know where they came from before leaping in. The Underfall Yard was their sixth album, by which time they'd perfected the Big Big Train sound, but the first with vocalist David Longdon, so it's the perfect place to start – and if you have Spotify, it won't cost you to give the band a try.

If you're feeling adventurous, here's the video for the first track of the new album.

Random scans this week are another brief set of Pan covers by Carl Wilton. I did a bit about Wilton a few months ago and these are a handful of scans I missed posting at the time. They show how varied his work could look within the framework of Pan's favourite brief: "Can we have the big head of a woman. Yes, a woman.... Big. Oh, I dunno... maybe a third of the space under the title. Yes, that big."

More from Roger Perry next week plus whatever else I can squeeze in... have a lovely bank holiday on Monday.

As I usually tackle a lot of mail in the morning, I tend to keep things fairly quiet so I can concentrate; the bits of your brain that interpret lyrics are also the bits of your brain that you need for writing, so anything spoken word or with lyrics can distract or, as I've found in the past, go through one ear and out the other without making any impact. I once listened to a whole 90 minute Agatha Christie mystery drama and at the end of it I had no idea who had been murdered, let alone who the murderer was.

In the afternoon I'm often revamping press releases, sorting out artwork and putting together material for the Hotel Business website, which requires less intense concentration, so I'll play music or listen to podcasts. I've mentioned the latter relatively recently, so I'll limit myself to mentioning that the second part of the latest epic from The Secret History of Hollywood was released recently—part two of the history of Warner Bros and the gangster cycle of movies starring the likes of James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson. The two episodes so far amount to about 10 1/2 hours of listening, and if you have any interest in old Hollywood, they're well worth it. Check out some of the other episodes about the Universal horror movies, Basil Rathbone's Sherlock Holmes and the life of Alfred Hitchcock... they're all worth listening to.

Easier on the ears, even when I'm trying to concentrate, is music. I've always been a fan of rock at the harder end of the spectrum, but I've mellowed—or "mellotron'd"—over the years and my tastes for extended listening these days are towards the progressive end of rock. (That "mellotron'd" gag is for other prog fans!)

Two of my favourite bands have albums out today. I mentioned a couple of week's ago that I was ridiculously excited that Frost* have a new record coming out. At the time of writing, I'm still waiting for my pre-ordered copy to arrive.

What I forgot to mention was that Big Big Train also have a new album out. Their last, English Electric, was my favourite album from a couple of years ago. For Folklore they've expanded their cast of musicians to include a violin player and additional keyboards. The results are a delight. There's a very good review here, which notes some weaknesses in the album (it's not quite up to the sublime brilliance of The Underfall Yard or English Electric) and, as reviewer Brad Birzer puts it, "Folklore is not the easiest of BBT's releases to grasp, nor is it their best. Regardless, it is incredibly good."

This leaves me in something of a dilemma... to recommend you all rush out and buy Folklore or to say rush out and buy The Underfall Yard and English Electric and then come back to Folklore. I think the latter. It's a progression of the band's sound and you need to know where they came from before leaping in. The Underfall Yard was their sixth album, by which time they'd perfected the Big Big Train sound, but the first with vocalist David Longdon, so it's the perfect place to start – and if you have Spotify, it won't cost you to give the band a try.

If you're feeling adventurous, here's the video for the first track of the new album.

Random scans this week are another brief set of Pan covers by Carl Wilton. I did a bit about Wilton a few months ago and these are a handful of scans I missed posting at the time. They show how varied his work could look within the framework of Pan's favourite brief: "Can we have the big head of a woman. Yes, a woman.... Big. Oh, I dunno... maybe a third of the space under the title. Yes, that big."

More from Roger Perry next week plus whatever else I can squeeze in... have a lovely bank holiday on Monday.

Wednesday, May 25, 2016

Perry's Picture Post part 8

1969

Due to the demise of Century 21 Publishing (Books) in June, I’d been cajoled into having a three week “period of rest” before securing employment with Hamlyn Books. Hamlyn Publishing by this time had moved out of London and was now ensconced in a high-rise office block that had gone under the name of Hamlyn House. Upon arrival, I was pleasantly surprised to find that John Kingsford, Brian “Benny” Green and Chris Spencer – all of whom I had once worked alongside at 96 Long Acre – were already in situ and, as old hands, were magnanimous in helping me settle in.

At Hamlyn Books, I had again rather fallen on my feet, although I found the environment I was now in most depressing when compared to my carefree days on Girl and the three years I’d had with Bob Prior and all those others I have spoken of.

There were roughly 40 designers occupying the open-plan 8th floor of Hamlyn House, who were working on a wide range of titles from cooking and gardening to how to care for your pet. There was also a brand new series covering all sorts that went under the heading of Hamlyn All-Colour Paperbacks, plus the odd book thrown in for good measure on how to test your dog’s IQ!

Although I remained at Hamlyn’s for about fifteen months, I never acclimatised to their hierarchical system of Cowboys and Indians, which I did my very best to ignore. The Art Director was Roger Garland who was permanently holed up in his office along with his female assistant. It would not have surprised me had I discovered that she was in possession of leather underwear, ropes, handcuffs, whippy canes and other forms of sexual-inducing torture, and that she had been placed in charge of Hitler’s Nazi Youth Movement. I do know that Garland designed diaries for Letts on a freelance basis, but apart from that, I have no idea what he did with himself all day long (in fact, I’m not altogether sure that I really want to know anyway).

Under him was Studio Manager John Youe. Youe also remained permanently in his office from morn to night, but at least he had an assistant named John Howard who had a commanding position overlooking the department as a whole and who, presumably, passed on any morsel of news worth mentioning to his boss.

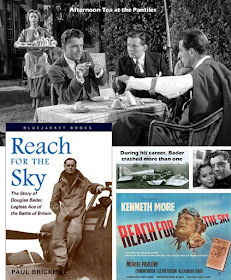

I actually got to know John Howard quite well for he and I soon shared driving and cars when going to and from work, until, that is, his carefree driving on a hot sunny evening with the roof folded down had ended up with much of the driver's side of the car sheered off and the two offside wheels becoming virtually square-shaped. It was a bit of a shame really as the spot he’d chosen was right outside “The Pantiles” nightclub and restaurant close to Bagshot on the A30, where war ace Douglas Bader had met waitress and wife-to-be Thelma Edwards. (Reach for the Sky with Kenneth More and Muriel Pavlow is one of my favourite movies!)

We then had the Art Editors, of which there were eight, who spent their days chatting amongst themselves and drinking copious amounts of tea or coffee. Installed on each floor was a tea/coffee/hot chocolate dispensing machine installed by the management and anyone with a thirst could help themselves to a plastic container of free beverage whenever they wanted.

My Art Editor from this little cluster of cowboys was Brian Cullen, a pleasant enough guy in his mid-thirties who popped pain-killing tablets by the box-load for a gammy leg he’d succumbed to several years earlier from a motor-cycling accident. By the odd way he walked and stood, it was clear that the damaged appendage was being held together with metal rods, leather straps and the odd spring or two. I first knew of Brian Cullen when ex-Eagle designer Ron Morley worked alongside him on Fleetway annuals, in the days when George Beal ran the section in offices above Covent Garden Underground Station.

In a side office adjacent to the Art Editors, we had Bill Brott whose job it was to buy all the art that went through Hamlyn Books and who received all the colour-corrected proofs as they came in from the various repro houses. The most endearing thing about Bill was his enormous nose, which dribbled unabated morning, noon and night. It came accompanied by a great deal of sniffing and a quick wiping from a very large white spotted red handkerchief (of which he must have had quite a good supply of).

And finally, tucked into a small corner – which wasn’t really a corner at all for it was actually halfway down the room, wedged between the window and an internal 18”-square supporting structure – were ex-Eagle designer Brian “Benny” Green and his assistant, John Kingsford. Kingsford had been Eagle Art Editor John Jackson’s Number Two all the time I worked on Girl magazine (you may remember that I spoke of John Jackson in Part One).

On the Tuesday – my second day there – Benny came over and asked if I would care to join both him and John Kingsford for lunch . . . particularly as he’d had an idea that he wanted to put past me. Benny was in charge of the Christmas Annuals Section, producing 24 books each year (an average of one book every two weeks), which for all intents and purposes was the same job I had been doing for the previous three years at Century 21 Publishing.

The three of us had gone to a small cafeteria in the nearby precinct during which time Benny had suddenly blurted out: “Hey Rog, how would you fancy having my job?” It was probably something he had been bottling up ever since he told his wife Amanda that I had come onto the Hamlyn scene. I naturally replied that I would be honoured to be given the chance and, going by the smiles all round, it would appear that I had given both Benny and John the answer they had been hoping to hear.

Following on from his days when he worked in the same office as Chief Sub-Editor of Eagle, Dan Lloyd and “Madge” Harman (this can be read in greater detail on “Bear Alley – The Men Behind the Flying Saucer Review” particularly parts 4 and 5 dated Thursday, October 31, 2013 and Saturday, November 2, 2013”), as a sideline, Benny had become the proud owner of an occult bookshop that was situated in Crystal Palace, just a few miles to the south of London. Benny knew that I could do his job standing on my head, and it was pretty clear that he had been keen to move on to pastures new.

During that Tuesday afternoon, Benny had not only given his boss Brian Cullen (and the Studio Manager John Youe) a glowing report of my past capabilities, but had also handed in his notice. Even more surprising was the fact that when he departed at 5 o’clock that same day, due to having been owed a fair amount of holiday time, it was with some sadness that I never saw Benny ever again – too late now as he passed away after having succumbed to an undisclosed short illness in October 2015.

Having been handed Benny’s job on a plate, I decided that it would be prudent if I laid down a few ground rules right from the very start. I’d said to Bill Brott (with Brian Cullen listening in) that at Century 21, I had commissioned all the artwork that had gone through my hands and that incidentals such as colour-correcting proofs had also been within my domain. With nods of agreement all round, they both conceded saying that with something so complex as Christmas annuals, perhaps it would be best if I carried on doing what I obviously knew.

Following his somewhat rapid disappearance from Century 21 Publishing, Bob Prior set up a packaging business along the lines of Leonard Matthews’ Martspress. But the two operations were as different as chalk and cheese. Whereas Matthews’ outfit had had a touch of class about it, the one Bob had run very definitely had been a far, far seedier operation for all sorts of reasons. First of all, due to the break up of his marriage, he spent most nights sleeping under his desk in the office. Secondly, during those times when he needed the assistance of a designer, despite me living in Farnham, Surrey (some 50-odd miles from the centre of London), it was still worth his while to drive out to my house where my wife Jenny had kept a bed constantly made up for any sudden arrival that he might wish to make—this being usually around 9 p.m. or 10 and when I invariably had to remain awake for half the night when all I really wanted to do was to go to bed and sleep!

One of his regular commissions was to produce a four-page tabloid newsletter for the Radio Luxemburg 208 Club. It was what they call a “premium product” meaning that the advertising revenue paid for the typesetting, the newsprint and the printing of it, so it had become a freebie, given away for no charge.

The printer Bob engaged had a small printing press situated about halfway down Ruislip High Street, and Bob had called in on his way to Farnham to iron out any problems that might have arisen. Now it just so happened that rain – strong enough to have closed nearby London Airport – had begun to tip down unmercifully, and a girl wishing to get home had backed her car off Ruislip’s wide paving area and the two vehicles had momentarily “kissed”. Through the torrential downpour, Bob had shrugged his shoulders and indicated to the girl that, with the rain being what it was, it wasn’t worth getting soaked for. So she drove off and Bob made to follow in the same direction. However, after little more than five or ten yards, the off-side headlight on Bob’s rusting mini fell out of its retaining orifice and, due to his car having run over it, the front tire became deflated within milliseconds. So Bob had no option but to get out and get soaked anyway.

In changing the wheel, the nuts had been so rusty that stud No. 2 had simply sheered of . . . and it was then that Bob decided to call out the AA, which he did from the printer’s office. After about two hours, the AA patrol-man finally turned up; took one look at Bob’s front wheel and said:

“I’m not touching that; its more than my job's worth!”

And with that, he got back in his own van and had driven off into the night.

So, with little or no option, Bob had to do the job himself and, fortunately, there had been no more sheering off of any further studs. But it did mean that he didn’t arrive at my house until nearly 11:00pm, which was when I’d had to start working on Bob’s freebie paper . . . and it was far from the type of design-work that gives me any pleasure.

Jenny had already turned in for the night and after fifteen minutes or so, Bob, too, had disappeared . . . into our downstairs toilet-cum-shower-room, where he remained for a good long while. I’d assumed that he was having dietary problems as he really wasn’t eating all that well, but had thought no more about it. It was a good thirty-to-forty minutes before he rejoined me at the dining table. Bob said nothing and I said nothing, and we left it at that.

A couple of years later, he decided to come clean. It would appear that Bob had been so thoroughly knackered that he needed to put his head down somewhere even if it was for only five minutes. He’d lain down on the floor with his head jammed between the toilet bowl and the shower tray and woken with a jolt just seconds before re-joining me. He’d been too embarrassed to tell me what had happened. It was rather silly really, as he could easily have gone to his made-up bed in the spare room . . . I wouldn’t have cared. It wasn't as if he was actually doing anything when he was with me.

(Incidentally, I apologise for the family shot below, but it's the only one I have of the dining table where I worked on Bob’s 208 Club freebie . . . however, may I draw your attention to the two bowls that Rae and Marcus are eating from; they are the bowls from the Candy and Andy set spoken of in Part Five)

It must have been late October or early November that Bob called through to ask if I could meet him with my cameras at the Serpentine Lake in Hyde Park. I know that it must have been about then as most of the leaves had already fallen from the trees. He’d come up with the idea of producing photo-strip stories whereby the individual frames were photographed rather than being drawn by an artist. Utilising the services of two “resting” actors (both in their early 20s), ultimately I produced a six-page dummy from the photographs I’d captured of the pair. It was a Boy meets Girl type of situation whereby the couple, having first met on the tree-top walkway (photographed at Battersea Park) had ended up by having a snack at the Serpentine lake-side restaurant.

With the presentation dummy now finished and complete with speech balloons, Bob touted the work around to various publishing houses including Fleetway and D C Thompson’s. And yes, editors were interested and yes, Bob did pick up some commissions, but with the idea now out of the bag (and free for all to use), the floodgates had opened and very quickly, dozens and dozens of teenage magazines had latched onto this idea. Soon after, everyone was doing very much the same thing.

As a sort of post script to all this – particularly having just spoken of The Serpentine – every two or three months, I had a strange individual call in to see me. He was an artist, but he’d supplied me with those very simple line drawings that one tends to see in cheap and cheerful colouring books. When he came – which was usually unannounced – he would hand over fifty or one hundred of these illustrations which I just added to the stockpile.

Mr Mayle was tall and thin; wore a shabby mackintosh both summer and winter, and trousers where the turn-ups were a good two-to-three inches above a pair of navy-blue plimsolls that clearly had seen better days. Much like Bill Brott, Mr Mayle always seemed to have a dew-drop poised upon the end of his nose, ready to drop.

Apparently, he swam the whole year round at the Serpentine alongside a group of his cronies, and he had been saying that, during the winter months, when feet and legs became numb through the intense cold, one had to keep a careful watch out that one hadn’t inadvertently kicked a submerged supermarket trolley, as if one wasn’t careful, you could easily bleed to death without even realising it.

Roger Perry

The Philippines

Coming soon: In Part Nine, one big step for mankind, the Clangers’ and lunchtimes with two-footed and four-footed friends in Richmond Park.

Due to the demise of Century 21 Publishing (Books) in June, I’d been cajoled into having a three week “period of rest” before securing employment with Hamlyn Books. Hamlyn Publishing by this time had moved out of London and was now ensconced in a high-rise office block that had gone under the name of Hamlyn House. Upon arrival, I was pleasantly surprised to find that John Kingsford, Brian “Benny” Green and Chris Spencer – all of whom I had once worked alongside at 96 Long Acre – were already in situ and, as old hands, were magnanimous in helping me settle in.

At Hamlyn Books, I had again rather fallen on my feet, although I found the environment I was now in most depressing when compared to my carefree days on Girl and the three years I’d had with Bob Prior and all those others I have spoken of.

There were roughly 40 designers occupying the open-plan 8th floor of Hamlyn House, who were working on a wide range of titles from cooking and gardening to how to care for your pet. There was also a brand new series covering all sorts that went under the heading of Hamlyn All-Colour Paperbacks, plus the odd book thrown in for good measure on how to test your dog’s IQ!

Although I remained at Hamlyn’s for about fifteen months, I never acclimatised to their hierarchical system of Cowboys and Indians, which I did my very best to ignore. The Art Director was Roger Garland who was permanently holed up in his office along with his female assistant. It would not have surprised me had I discovered that she was in possession of leather underwear, ropes, handcuffs, whippy canes and other forms of sexual-inducing torture, and that she had been placed in charge of Hitler’s Nazi Youth Movement. I do know that Garland designed diaries for Letts on a freelance basis, but apart from that, I have no idea what he did with himself all day long (in fact, I’m not altogether sure that I really want to know anyway).

Under him was Studio Manager John Youe. Youe also remained permanently in his office from morn to night, but at least he had an assistant named John Howard who had a commanding position overlooking the department as a whole and who, presumably, passed on any morsel of news worth mentioning to his boss.

I actually got to know John Howard quite well for he and I soon shared driving and cars when going to and from work, until, that is, his carefree driving on a hot sunny evening with the roof folded down had ended up with much of the driver's side of the car sheered off and the two offside wheels becoming virtually square-shaped. It was a bit of a shame really as the spot he’d chosen was right outside “The Pantiles” nightclub and restaurant close to Bagshot on the A30, where war ace Douglas Bader had met waitress and wife-to-be Thelma Edwards. (Reach for the Sky with Kenneth More and Muriel Pavlow is one of my favourite movies!)

We then had the Art Editors, of which there were eight, who spent their days chatting amongst themselves and drinking copious amounts of tea or coffee. Installed on each floor was a tea/coffee/hot chocolate dispensing machine installed by the management and anyone with a thirst could help themselves to a plastic container of free beverage whenever they wanted.

My Art Editor from this little cluster of cowboys was Brian Cullen, a pleasant enough guy in his mid-thirties who popped pain-killing tablets by the box-load for a gammy leg he’d succumbed to several years earlier from a motor-cycling accident. By the odd way he walked and stood, it was clear that the damaged appendage was being held together with metal rods, leather straps and the odd spring or two. I first knew of Brian Cullen when ex-Eagle designer Ron Morley worked alongside him on Fleetway annuals, in the days when George Beal ran the section in offices above Covent Garden Underground Station.

And finally, tucked into a small corner – which wasn’t really a corner at all for it was actually halfway down the room, wedged between the window and an internal 18”-square supporting structure – were ex-Eagle designer Brian “Benny” Green and his assistant, John Kingsford. Kingsford had been Eagle Art Editor John Jackson’s Number Two all the time I worked on Girl magazine (you may remember that I spoke of John Jackson in Part One).

On the Tuesday – my second day there – Benny came over and asked if I would care to join both him and John Kingsford for lunch . . . particularly as he’d had an idea that he wanted to put past me. Benny was in charge of the Christmas Annuals Section, producing 24 books each year (an average of one book every two weeks), which for all intents and purposes was the same job I had been doing for the previous three years at Century 21 Publishing.

The three of us had gone to a small cafeteria in the nearby precinct during which time Benny had suddenly blurted out: “Hey Rog, how would you fancy having my job?” It was probably something he had been bottling up ever since he told his wife Amanda that I had come onto the Hamlyn scene. I naturally replied that I would be honoured to be given the chance and, going by the smiles all round, it would appear that I had given both Benny and John the answer they had been hoping to hear.